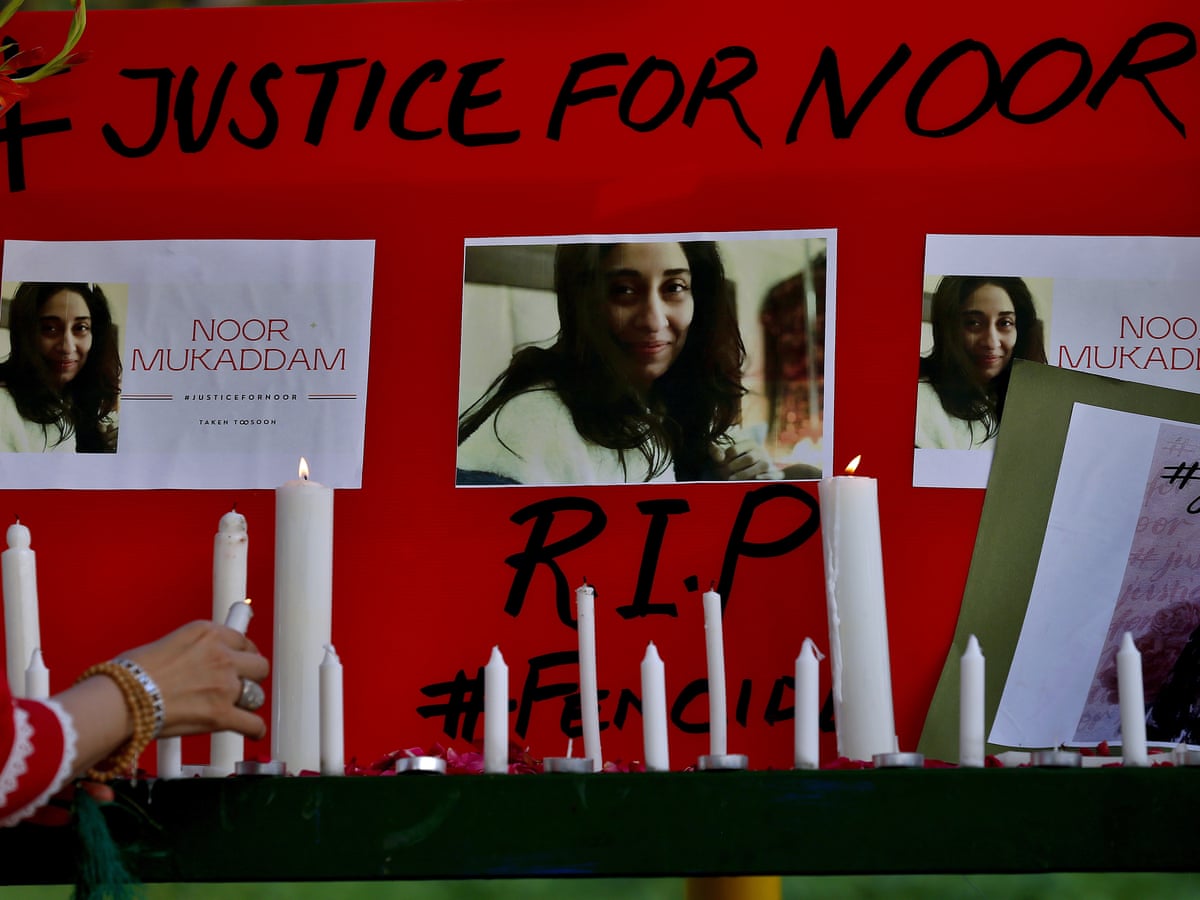

On 20th July 2021, Noor Mukaddam, a 27-year-old resident of Sector F-7/4, Islamabad, an elite area, was brutally killed. Her death did not come out of the blue; she spent two days in captivity, torment, torture, and rape in the hands of Zahir Jaffer.

Zahir Jaffer was no ordinary man, but a US national of Pakistani descent, the son of a wealthy industrialist family, someone who believed his privilege could protect him.[1] He held her at ransom when Noor turned down his proposal to get married. The CCTV footage further revealed that Noor was seen trying to escape twice, only to be pulled back inside.

She was tortured. She was raped, and then, she was BEHEADED!

Zahir Jaffer was caught at the crime scene, and the DNA confirmed the assault. The details of her murder stunned the whole nation and led to protests and social media hashtags, #JusticeForNoor. In February 2022, a session court sentenced him to the death penalty and 25 years of harsh imprisonment. The country breathed a sigh of relief, believing justice had been done.

But the story didn’t end there.

Zahir appealed. The case was taken to the Supreme Court. This was shaken in November 2025 when one of the hearings involved Justice Ali Baqar Najafi, who implied that the murder was a result of live-in relationships. He added that a live-in relationship was a rebellion against God and against the Pakistani law and Sharia.[2]

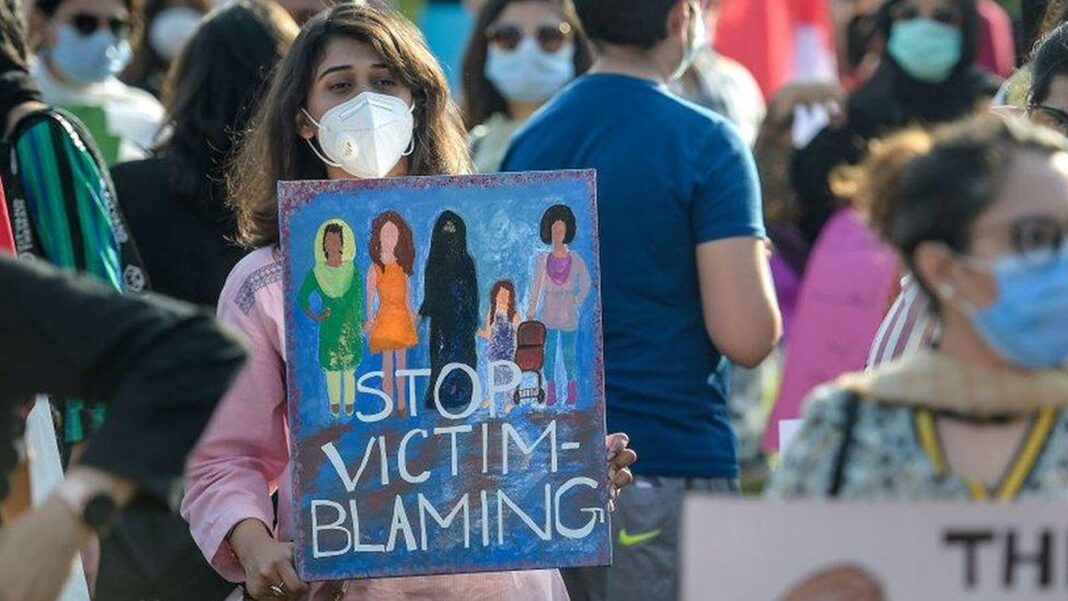

For many people in public, what he said was not just insensitive but dangerous. The fact that when a judge, in the highest seat of the legal system, puts an act of inconceivable brutality in the context of a punishment for a vice, resonates with a way of thinking always used against women. The same reasoning justifies honor killings, downplays women victims of domestic violence, and policing of women’s autonomy, including the clothing they wear and the places they visit.

Every day, women are murdered by their husbands, their relatives, their friends, colleagues, and even by strangers. They do not have a safe place: at home, at workplaces, or on the streets. It is not the choice of women that turns violence against women, but rather it is misogyny, entitlement, and patriarchy as a culture. It is important to understand that Noor did not get killed due to her visit to a person. She was killed by the decision of a man to kill her.

The comments made by Justice Najafi did not come out of thin air. This was reinforcing what is already feared by many Pakistani women, that misogyny can leak through the cracks of the justice system, even in a crime where the crime is obvious, the evidence is irrefutable, and the cruelty documented.

When this kind of narrative gets into judicial commentary, the damage is not metaphorical; it erodes trust. It gives a message to the victims that even when they are pursuing justice, they may still be held responsible. It informs offenders that society can seek reasons on their behalf.

Pakistan’s fight is not merely against criminals; it is against a certain mindset. A mindset that blames women for the violence they endure, that excuses men by moralizing their crimes, and that polices women’s autonomy more rigorously than men’s actions.

This mindset, time and again, transfers the burden of protection onto women rather than dealing with the violence itself. Until this change is implemented, justice will remain fragile. Nights like September 9, 2020, and the tragedy of Noor Mukaddam will serve to remind the nation of how far it has to go.

The Forgotten Battle: What Happens After Rape?

To a rape victim, the nightmare does not cease at the moment of the assault. The actual cruelty, in many respects, begins later. At police stations, corridors of hospitals, and courtrooms, where she is forced to repeat her story, relive her trauma, and defend her own innocence again and again.

Until 2021, in Pakistan, survivors were subjected to the degrading and unscientific two-finger test.[3] It was used despite lacking any forensic value and causing horrific physical and psychological damage to the victims.

Physicians would put one or two fingers into the vagina of a woman to ascertain “laxity” or the hymen, trying to determine whether she was sexually active or not. Some even claimed they could tell whether it was her first time, a myth modern science has long discredited. Yet for decades, this invasive test had been employed to challenge the character of a survivor, to discredit her, and to decide whether she was worthy of justice, by a test of purity as defining the truth.[4]

Justice Ayesha A. Malik ruled the practice unconstitutional in a historic and landmark judgment of 30 pages, declaring the procedure to demean the dignity of the female victim and a violation of fundamental rights, namely Article 9 (right to life) and Article 14 (right to dignity) of the Pakistani Constitution.[5] This verdict was a long-overdue victory, coming after generations of unreasonable misery.

Nonetheless, despite this development, the journey to justice remains dangerous. There are thousands of cases, both reported and unreported, that never receive justice.[6] The survivors stay quiet and are engulfed by secrets, fear, and a society that continues to blame them more readily than the offender.

Why does justice fail?

Most of the time, medico-legal reports are faulty, incomplete, or ill-written. DNA evidence is lost, contaminated, or not collected at all due to the unavailability of rape kits.

By law (Section 344A of the 2016 Criminal Law Amendment), rape cases must conclude within 90 days[7], yet in reality, they stretch to 250 days or more, often dragging on for years. During these delays, the system slowly suffocates the case. Witnesses are threatened into silence, and victims face social, familial, and financial pressure to withdraw. Files gather dust, cases quietly die.

That is the tragedy of sexual violence; the rape can take a few minutes, but the legal pain can take years. The perpetrator caused the initial wounds, but our legal system turns them into traumas. Justice can only be elusive until these structural failures are addressed, until evidence is maintained, trials are prompt, and survivors are treated with respect. Justice can not be attained until it is trapped behind bureaucracy, stigma, and a society yet to understand how to listen.

What Forensic Science Does in Rape Cases

Rape forensics is a branch of forensic science that is involved in the gathering of evidence, examination, and interpretation of evidence involving sexual assault. It entails biological, physical, and occasionally even psychological evidence that assists investigators in knowing whether a sexual assault occurred, who committed the crime, and what happened before, during, and after the attack.[8]

The type of evidence presented in sexual assault cases is numerous, and each piece of evidence is crucial in the reconstruction of what actually happened. The most important is the DNA that can be taken in the form of saliva, semen, blood, and skin cells that are present on the victim’s body, clothes, or other objects. DNA may involve a direct connection of a criminal to a crime and may be the most solid evidence in a courtroom.

Another significant group is related to fibers and hair, which can be transferred in case of physical struggle. These trace materials are capable of linking the victim and the accused together at the same point or place of contact. The presence, contact can be proved even by a single strand of hair or a fiber, in case other evidence can be challenged.

The medical notes and forensic photography are used to carefully record the injuries sustained during the assault. Pattern injuries, bruises, cuts, abrasions, bite marks, and other evidence of force and defiance silently speak volumes of a story of resistance. These documents maintain physical evidence that can diminish with time, and injuries are visible even after the recovery process has started.

The toxicology reports are a crucial aspect in drug-facilitated assault cases. Drugs used to immobilize the victim can be detected in blood and urine tests. This kind of evidence justifies memory lapses and refutes accusations that the survivor did so out of consent or because he or she was drunk.

The importance of Forensic Evidence

All these lines of evidence help to give an objective and scientifically proven backup to the account presented by a survivor. Forensic science becomes an objective partner in legal systems where the victim-blaming element, absence of witnesses, and social stigma tend to ruin cases. It moves the standpoint to the challenge of the survivor’s character to the analysis of facts, where justice lies.

The Forensic Medical Examination

The forensic medical examination is one of the most crucial elements of a rape investigation, and it can be performed during the first 72 hours following the sexual offense. In this test, the Rape Kit or Sexual Assault Evidence Kit (SAEK) is utilized to gather significant biological and physical evidence. [9]

The exam is administered by a Medico Legal officer (MLO), a trained professional who handles delicate procedures with both scientific precision and emotional sensitivity.

The Medico Legal Examination may involve:

- Mouth, skin, genitals, and anus swabs

- Collection of blood, urine, or semen samples

- Detailed record of injuries

- Photographs to maintain records of bruise or injury

Each sample is well labeled and closed to prevent contamination. Appropriate evidence gathering by an MLO increases the likelihood of identifying the perpetrator and of conviction in court. An entire forensic examination is not just beneficial to the law but also to validating the survivor’s experience, helping them regain a sense of control.[10]

The victim’s legal team relies on medical examination reports and witness statements; these aspects form the basis of the victim’s argument and show how scientific proof serves as a potent instrument of justice. Although fictional, the processes depicted are realistic forensic activities that make the drama not only entertainment, but a kind of civic education, illuminating the way for a survivor to navigate the complex overlap of medicine, law, and trauma.

Role of Forensic Evidence for Rape Survivors

Evidence in forensics is of central importance in enhancing the credibility of a victim. When an account by a survivor can be undermined by emotional distress, social stigma, or cultural prejudice, scientific evidence offers objective explanations. DNA reports, medical results, and toxicology results are found to guide the courts to concentrate on facts as opposed to the harmful assumptions about the character or behavior of the survivor.

Forensic documentation helps neutralize victim-blaming narratives that frequently prevail in rape case trials in Pakistan. When the injuries, biological samples, and medical records are collected and preserved correctly, they give a factual account of the crime that cannot be easily dismissed. This fact removes the blame from the survivor and places the responsibility on the rapist.

Psychologically, forensic examination can provide validation and emotional support to the survivors.[11] Being aware that their experience has been officially documented and scientifically proven can help overcome the sense of self-doubt, shame, or disbelief imposed by society. It proves one main fact: the damage inflicted is real, registered, and deserves justice.

But the best advice, given by experts, is to ensure that they report early (within 72 hours). Late reporting can supposedly be dangerous to a case. The fear of social backlash, family influence, and distrust towards the institutions and organizations usually makes the victims reluctant, and important evidence may either be damaged or lost. Immediate health care review and preservation of evidence further enhance the chances of accountability and minimize the chances of being denied justice by a gap in the procedure.

In Pakistan, forensic awareness, among women and families, health practitioners, and law enforcement, is not an option but a necessity. Knowing what to do once assaulted sexually may turn an otherwise collapsed case into a case that upholds scientific truth.

Conclusion:

In 2024 alone, according to a recent Gender Based Violence (GBV) report by the Sustainable Social Development Organization, 32,617 cases of GBV were reported. Over 5,339 cases were of rape. Despite thousands of cases, Pakistan’s conviction rate remains dismally low, at just 0.5% for rape.[12]

Violence against women in Pakistan is not just physical violence; it is a cultural, institutional, and systemic violence. Victim-blaming continues to overshadow criminal accountability. There is still a very low level of forensics awareness. Before any court can silence the survivors, families tend to do the same. Outdated beliefs still seep into judicial spaces where justice should be blind, but hope lies in knowledge.

The knowledge of what to do after rape, how to report, what forensic steps to follow, how to preserve evidence, etc., can become the strength of survivors and their families during the darkest moments. When used properly, forensic science is not merely an investigative tool, but a shield against bias, a weapon against silence, and the truth what survivor is screaming.

If Pakistan is to move forward, the responsibility lies with all of us to stop blaming victims, to insist on institutional change, to demand forensic integrity, and to build awareness, not in the wake of tragedies, but before them. Only then can we be confident that no woman on a highway, no woman trapped in the house, and no woman trying to get away from her murderer will ever feel lonely anymore.

References:

- https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-60514698

- https://dunyanews.tv/en/Pakistan/920348-noor-muqaddam-case-sc-judge-flags-livein-relationship-as-socie

- https://ohrh.law.ox.ac.uk/sadaf-aziz-v-federation-of-pakistan-the-end-of-virginity-testing-in-pakistan/

- https://www.cfhr.com.pk/our-work/the-use-of-the-two-finger-test-in-pakistan

- https://www.dawn.com/news/1599672

- https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/1287512-gender-based-violence-surges-with-dismal-conviction-rates

- https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Women/SR/RapeReport/CSOs/097-pakistan-2.pdf

- https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsigss.2013.10.023

- https://www.endthebacklog.org/what-is-the-backlog/what-is-a-rape-kit-and-rape-kit-exam/

- https://www.btp.police.uk/ro/report/rsa/alpha-v1/advice/rape-sexual-assault-and-other-sexual-offences/forensic-evidence-rape-sexual-assault/

- Dalenberg, C. J., Straus, E., & Ardill, M. (2017). Forensic psychology in the context of trauma. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0000020-026

- https://www.dawn.com/news/1894972

More from the author: Crime Scene Investigation, Clickbait, and Screens: How Media Reshapes Forensic Reality

Anam Ilyas holds an MS Forensic Chemistry from Government College University, Lahore. She is a science enthusiast with a great love for explaining complex topics in simpler ways. She aims to bridge the gap between scientific research and the general public through her writing. When she is not writing or talking, you can find her lost in a book or making ideas come alive through her drawings.

very informative articles or reviews at this time.

This is my first time pay a quick visit at here and i am really happy to read everthing at one place

Comments are closed.