Astronomy, for many centuries, has educated us about the wonders of the cosmos. From the first discovery of a supernova in Cassiopeia (a constellation) by Tycho Brahe to today’s powerful telescopes, such as the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) or the James Webb, humanity has made significant technological advancements within the realm of Astronomy. As this discipline has evolved into a global multi-billion dollar industry, questions have emerged about how to sustain excellent research while considering its environmental impact.

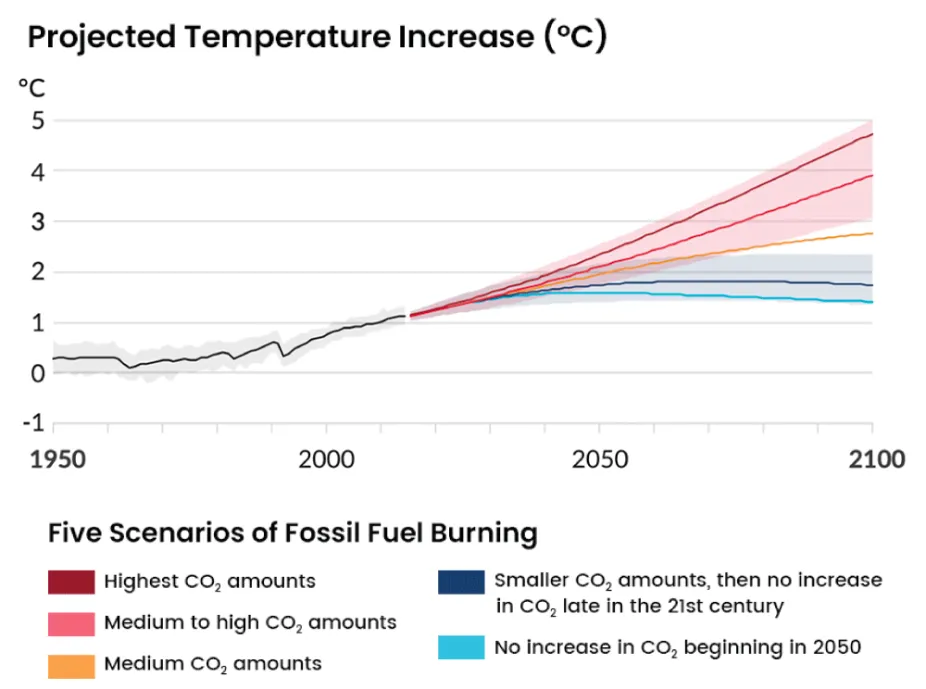

Climate change is the most pressing issue humanity faces today, and it is the responsibility of the residents of this only known living planet to nurture and take care of our homes. To avert the crisis, we all should play our roles, especially scientists, in acting upon what is necessary for the environment and engaging in proper advocacy for environmental sustainability as responsible citizens.

A group of astronomers took matters into their own hands and estimated the carbon footprint of astronomical research on the climate of Earth. Hence, it became the starting point for the formation of an organization called ‘Astronomers for Planet Earth’ (A4E). A group where astronomers, using their unique astronomical perspective, mobilize researchers around the world to address the present climate crisis.

Here, we are happy to share our conversation with one of the founding members of A4E, Dr. Leonard Burtscher. He sheds light on the organization’s mission and the importance of understanding astronomy’s carbon footprint.

Aly: Beginning with – could you share about your work and elaborate on your area of research as an astronomer?

Leo: I worked in astronomy for 15 years, during which time I completed my PhD in Infrared Interferometry. Subsequently, I joined the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Garching at Munich, where I contributed to the development of the new instrument GRAVITY, which led a role in winning the Nobel Prize for my research group leader three years ago. After that, I became a staff scientist at Leiden University, working on the new ELT instrument, METIS. METIS is a mid-infrared instrument designed to characterize Earth-like planets and study active galaxies, which has been my primary focus.

However, this is my past to some degree. Approximately one year ago, I switched the courses completely. I am now an energy and climate policy advisor at a small NGO, a non-governmental organization called the Umweltinstitut – The Munich Environmental Institute.

In the past three or four years, I realized that studying distant galaxies and dusty clouds around supermassive black holes, while fascinating, was no longer aligned with my interests. Therefore, I joined this activist group and essentially trying to reduce energy consumption in Germany, which is currently one of my main priorities.

Aly: Nice! Can you highlight what ‘Astronomers for Planet Earth’ A4E is all about, its mission, and how it came to be? I assume that it has an interesting story behind its formation.

Leo: A4E is now over four years old and stands as the only, and certainly the largest, grassroots organization in astronomy dedicated to sustainability. It was created simultaneously at two locations. The first group, predominantly centered in San Francisco and Yale University, was made up of individuals such as Adrienne Cool and Debra Fischer, who had long been part of the AAS Sustainability Committee for the American Astronomical Society.

The second group, based in Europe, coalesced a few months later and jointly called ourselves‚ ‘Astronomers for Planet Earth.’ They initiated discussions on the social media platform Twitter during the European Astronomical Society annual meeting in Lyon, France, in 2019 — an event marked by a heatwave. The University of Lyon, where the meeting took place, lacked air conditioning, so it was very hot in all the meeting rooms. Not as hot for Pakistani conditions, probably, but hot for European conditions

Some of us began to argue about whether astronomers were part of this problem with frequent flying and extensive use of supercomputing. That is when we said, okay, we need to look into that and improve it by recognizing the need to first reduce the carbon footprint of astronomy itself. Our conviction was grounded in the belief that taking personal action was a prerequisite for advocating change to others.

Therefore, from the beginning, A4E outlined a four-year plan with two central pillars. The first involved reducing the carbon footprint of astronomy research, and the second aimed at utilizing astronomy to communicate what they termed the “astronomical perspective.”

This perspective was inspired by the iconic image from Voyager 1—the ‘pale blue dot,” where we can see a tiny dot representing Earth from far away out of our solar system, all that we have, as Carl Sagan so beautifully wrote.

“Hence, we see ourselves as the Climate Voice in Astronomy. But also, the Astronomy Voice in the Climate Movement.” That’s how I would describe what A4E is and does.

Aly: It is all about realizing and making astronomical research sustainable. Quite fascinating indeed. A very strong message is visible from nearly all A4E campaigns: “There is no PLANET B”. Certainly, it’s not just a catchy and attractive phrase but the truth. Can you tell me more about how astronomers came to this realization and why you think it is important to emphasize?

Leo: Certainly, one of the statements we, as scientists, aim to affirm, which is often shown at climate demonstrations, is true, and it’s astronomical science that says this.

Astronomers have discovered planets outside our solar system in recent years. The discovery of ‘51 Pegasi b’, where the Nobel Prize was given to Michael Mayor and Didier Queloz in 2019. The Kepler mission further accelerated this revolution, revealing over 2600 exoplanets, and today, our knowledge extends to more than 5,500 planets outside our solar system. Some of these distant worlds bear similarities to Earth, with intriguing atmospheres that could potentially support life, including planets with oceans—a captivating prospect.

However, the story behind Planet B is that, even if you find another planet that’s just like Earth, there’s a catch: you have to be able to get there, and for a scientist, it’s always very clear that this is impossible likely for centuries to come. Therefore, as scientists, we emphasize to the public that while exploring exoplanets is fascinating, it should not be viewed as an alternative to safeguarding our planet.

It is crucial to convey this message and use it as a powerful motivator for discussions on sustainability. The increasing fascination that people have with astronomy makes it an ideal catalyst for encouraging contemplation about our place in space and how unique Earth is. That is why the No Planet B story is so good praise for astronomy.

Aly: Yes, you are right. I will say that the pandemic, on a positive note, was an eye-opener. It showed the astronomy community that online meetings are viable, significantly reducing flight emissions.

It is really important to understand the Carbon Footprint of Astronomy. Could you explain how big the carbon footprint of astronomical research is and how it is affecting our climate?

Leo: I will say that there are some caveats with computing accurate carbon footprints because that requires thorough research. While some researchers, including myself, have delved into this realm, it’s crucial to acknowledge that not all sources of emissions are always accounted for. What is relatively easy to compute is the emissions from flying to conferences. Knowing where people come from and which mode of travel they use, one can compute the emissions for a conference.

Together with my colleagues, I conducted such calculations for the 2019 Meeting in Lyon and the 2020 online European Astronomical Society meetings. We found that the difference in emissions between the in-person and online meetings was a factor of 3000. A single round-trip flight within Europe amounts to roughly one ton of emissions, with even higher footprints for those traveling from Asia, Australia, or the US.

However, even in this seemingly straightforward calculation, there are discussions surrounding the impact of airplane emissions, considering the radiative forcing index. C02 emissions released at high altitudes have different effects than C02 emissions on the ground. Additionally, planes have contrails that have effects that are not fully understood.

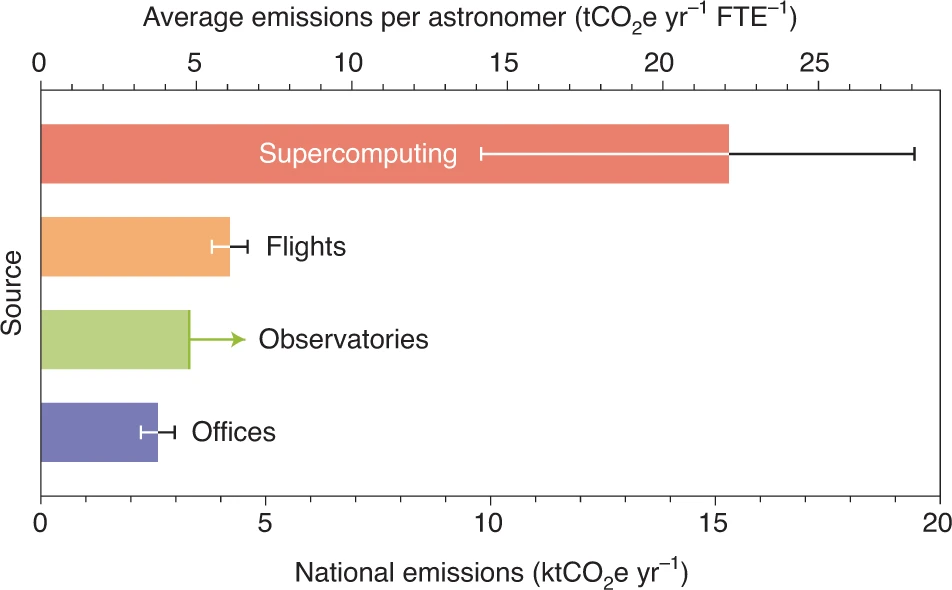

Expanding the analysis to the institute level involves accounting for heating, electricity, commuting, and possibly even food emissions. Supercomputing also contributes to emissions, depending on the power source of the supercomputer.

In a comprehensive analysis catering to all the institutes in the Netherlands, we found that total emissions per staff researcher ranged from about 3 to 10 tons per year of CO2 equivalent emissions, including the radiative forcing index for flights.

A more recent study by Jürgen Knödlseder evaluated the carbon emissions of astronomical infrastructure, considering all the necessary concrete and steel. This analysis revealed the emissions were 37 tons of CO2 equivalent per year per astronomers (with quite some uncertainty due to the estimation method). Still, this is probably the single largest source of emissions for astronomy research. We should consider these emissions when discussing new astronomical infrastructure e.g., do we need three extremely large telescopes, or would two be sufficient if we focus more on collaboration instead of competition, perhaps?

We can see from these papers that it’s a bit hard to pin it down to one number.

One of the earliest papers addressing the carbon footprint of research activities initially found a very high carbon footprint for research done in Australia, reflecting the country’s heavy reliance on coal for electricity production. Later, the number was updated when their utility switched to a cleaner form of energy, and the carbon footprint was suddenly a lot smaller, although they used the same machines.

Therefore, it depends on the location and which sources and scopes of emissions you include. One widely accepted carbon accounting standard is the greenhouse gas protocol. “The answer is complicated, but as a rough number, I would say something between 5 and 30 tons currently is probably the carbon footprint per astronomer per year, just for astronomy work!”

Aly: When you first started this initiative and went to the public, how did people react to this idea?

Leo: Among other astronomers, we had mostly positive reactions. When discussing our goals of measuring and reducing our carbon footprint and enhancing public communication, many expressed openness and acknowledged the importance of taking action. They eventually realized that we cannot go on and fly around like crazy and do nothing; we need to take active measures ourselves.

Unfortunately, some institutions, including professional societies, were not as open to embracing this change. They saw the difficulties in changing their meeting format. Sometimes, they see financial challenges in doing hybrid meetings, where they think they need to spend a lot of money to implement these. However, much more economical ways of implementing hybrid meetings are available and have been tested successfully. The European Astronomical Society, for example, shifted back to in-person meetings, expressing a belief that online meetings alone may not align with participants’ preferences. The reactions, therefore, were a bit mixed.

Organizations like the European Southern Observatory (ESO) have taken steps toward sustainability by installing solar panels for telescopes in Chile. Another site, La Silla, has already had a photovoltaic plant for a couple of years. However, they’re having a hard time being smart about flying for observations. While there have been improvements, the pace and extent of change have not met the rigorous standards advocated by A4E.

Aly: Apart from the engaging videos I have seen, what other initiatives or projects have A4E undertaken to advocate the seriousness of the climate crisis? How one can approach spreading this message effectively?

Leo: Activities under the A4E umbrella, apart from these videos, several publications have been produced, including two special issues in Nature Astronomy. Ongoing work, led by Andrea Gokus, is delving into flight emissions of astronomers in 2019 on a global scale, analyzing correlations between emissions, conferences, and the wealth of the country where the astronomers are from.

We also organize events at society meetings, collaborating with entities such as the American Astronomical Society (AAS) Sustainability Committee and the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. Special A4E-themed meetings have addressed astronomy and sustainability, featuring discussions with climate scientists, experts in light pollution, and representatives from telescope consortia sharing strategies to minimize emissions.

One of the biggest activities we initiated was an open letter to astronomy institutions and societies calling upon them to become active and to do whatever is in their power to reduce emissions. The letter gathered approximately 3,500 signatures within a few weeks, being quite successful.

More recently, A4E has engaged in localized outreach efforts, such as organizing an astronomical organ concert in Germany. This unique event combined the powerful experience of organ music with compelling videos from A4E, evoking emotional responses from attendees. Such events aim to convey the urgency of environmental stewardship and emphasize a positive narrative.

Our key focus is shaping a climate change narrative that goes beyond scientific facts. Recognizing the need for adaptation, the organization advocates framing this change positively. The aim is to frame this narrative not as a loss of conveniences like flying or fashion but as an opportunity to protect the planet and still ensure a high quality of life for all. By sharing this story, A4E endeavors to inspire positive action and a collective commitment to environmental preservation. This is what we all should try to do.

Aly: As we wrap up our conversation, I would love to hear your advice for members of the astronomy community who are eager to spread this positive message about sustainability. What individual actions would you recommend to help tackle the climate crisis?

Leo: Quoting one of the climate communicators in the US, Katharine Hayhoe, who advocates for a climate positivity movement, emphasizes the importance of talking about the climate crisis. The idea is to ensure that individuals don’t feel isolated with their concerns but connect with others to collectively address the challenges. As an individual, you can very quickly get the impression that there’s nothing I can do. While one person may feel limited in what they can achieve, the power lies in the collective effort of many individuals coming together. Some positive examples of movements started with something small, but with a group, they changed the world for the better.

This is the kind of hope that I would like to share with people, and I hope that you’re not alone with this, and this is also what A4E is for. We have a platform to foster this connection and maintain a network where people can share information, resources, and insights. One of the most important aspects of A4E is that it helps people feel like they are not alone and tackle these huge problems as a collective team.

As individual astronomers, the best thing we can do is share the astronomical perspective, particularly the ‘Pale-Blue-Dot’ story. A4E encourages various creative ways to communicate this perspective, such as organizing astronomical organ concerts or hosting discussions during mountain hikes. The key is to incorporate elements that connect astronomy to the broader story of our place in the universe and the importance of protecting our planet. Whether through dance, music, traditional talks, or online meetings, the overarching message is to get people thinking about our place in the universe, about our place on Earth, and that it’s probably a good idea to protect this planet for a little while longer.

Also Read: LITTERBUGS IN SPACE: THE NEXT FRONTIER FOR CARBON FOOTPRINTS?

Aly Muhammad Gajani holds a Master’s degree in Space Science and Technology, specializing in Astrophysics together with GIS applications. His research focuses on galaxy evolution, astrophysical cosmology, exoplanet detection, and computational astronomy.