The world knows Albert Einstein as a genius — the theory of relativity, his mass–energy equivalence formula E = mc2, and his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect have all immortalized him in the annals of history.

But Albert could never have become Einstein without his first wife and college sweetheart, Mileva Maric.

Mileva was a physicist of note in her own right — some even go as far as to argue that she was perhaps a better scientist than Einstein himself. Born in 1875 in Titel, (modern day Serbia), Mileva belonged to an affluent family of Serbian descent. Mathematics and physics were her passions and such was her intellect that even in those times, she was allowed to attend an all-boys’ school in Zagreb as a teenager to pursue her intellectual passions.

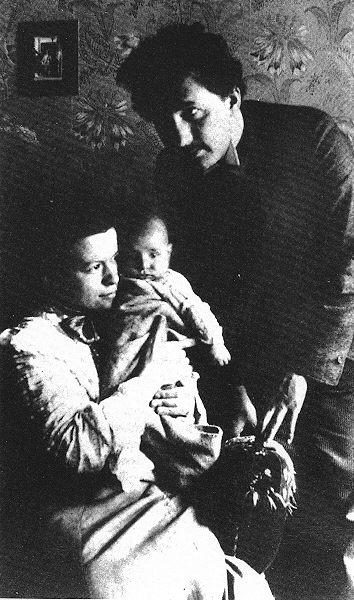

From Zagreb, Mileva moved to Zurich to enroll at the Zurich Polytechnic School. She was the only woman among the six students enrolled in the course. It was here that she met a young German student named Albert Einstein. Their shared love of science eventually resulted in them striking up a romantic relationship. Some years later, they got married. Albert is said to have relied on Mileva’s brilliance for his work although recent scholarship explains that he never gave credit to her for her ideas.

But for many years, Mileva stayed at home while Albert worked in a different country and travelled far and wide for professional purposes. Although they had three children — Lieserl Einstein (1902–1903), Hans Albert Einstein (1904–1973) and Eduard Einstein (1910–1965) — the relationship collapsed and two scientists went their separate ways. Albert would remarry in 1919, this time to his cousin Elsa Löwenthal.

On Einstein’s 140th birth celebrations, the Scientia Pakistan team brings a side of Albert Einstein that remains unfamiliar territory to many: Einstein’s relationship with Mileva Maric. We are reprinting a selection of letters exchanged by Mileva and Albert (preserved at the Princeton University Press as part of The Digital Einstein Papers). Through these letters shared by Mileva and Albert, we discover how the flame that once burned bright was eventually extinguished by the pressures of a long-distance relationship.

From Mileva Maric

[Zurich, after 7 July 1901]

My Darling,

Again I was unable to reply for an eternity to your dear little letter. I did want to write you immediately, but you know how much I am suffering now and this afternoon I had such a severe headache that I had to lie down. I’ve already become an utter whiner of a little mother. But now I’m feeling very well again.- So Drude also has let something be heard of him, he really is a splendid fellow. How the gentlemen do pay court to one another; I mean, the way he speaks about Boltzmann, that he believed he must have done it right. Naturally, a Boltzmann!

So, sweetheart, you want to look for a job immediately? and have me move in with you! How happy I was when I read your little letter, and how happy I still am and always will be, as well. And I’d give my head if my happiness wasn’t contagious to you as well, sweetheart! But of course it really mustn’t involve the worst of positions, darling, that would be too hard for me, I couldn’t stand it. Our various elders are going to be amazed, now. Incidentally, my sister wrote me that I really should invite you to visit us during the holidays; my old folks are probably in a better mood now. Wouldn’t you like to come along just for a while? I would be pleased! And imagine the wonderful trip we’d be taking there together! We would get off every so often and go on foot a bit or make brief stops. And then at our place everything would be new to you. And when my parents see us both physically before them, all their doubts will evaporate.

The Einstein family’s home in Novi Sad, Serbia

Did you have a nice time in Lenzberg? On Sunday there was such a terrible thunderstorm, I was constantly afraid you might still be en route. But I hope you were already safely under cover, sweetheart. I did still want to give you cherries, you know, but you wouldn’t have been able to carry them to L[enzburg] anyway. Now they’re waiting for you, nicely locked away. I am being very industrious, I still have to study Weber astutely now; and in between I’m constantly looking forward to Sunday when I can see you again and kiss you, really and truly, not just in my thoughts, and deeply, as it comes from my heart, and everywhere all over.

What are you up to, sweetheart? Is the weather there as dreadful as it is here? When you come on Sunday, do also bring your little fiddle along, and in any case, just write when you’re coming so that I can expect you.

But now, my greetings and kisses from the bottom of my heart, and write back soon. Yours,

D[ollie]

Miss Popova is jealous of me about Miss Engelbrecht, which naturally amuses me, and whenever we 3 meet she gets annoyed.

To Mileva Marie,

Bern. Saturday evening. [28 June 1902 or later]

My little Darling,

I am in high spirits, having just arrived from the Garden with Ehrat and Solovini, and a young man whom I know from Schaffhausen and who had come along to Bern just in order to visit me. Tomorrow I’m going to the Beatenberg near Thun with them, and they will be leaving on Monday, which suits me just fine. I would much rather be going to the Beatenberg with you than with a bunch of men; after all, I’m a man myself.

You can’t imagine how tenderly I think of you whenever we’re not together, even though I’m always such a mean fellow when I’m with you. But just you wait: next Sunday, or the Sunday after that, we, too, will make an excursion, and we will leave already on Saturday evening! Then, in the evening and at night, I will kiss you and squeeze you again to my heart’s desire.

Ehrat suffers quite a lot from his bad nerves, even though he has a very agreeable life. Imagine if he had my job! I don’t think he would be able to stand it for even 14 days. He should really have a sweetheart like I do, who’ll love him and bring some poetry into his life, so he’ll realize that one can have a life that’s full of good cheer and tender feelings, instead of wearing a constant frown upon one’s face.

Goodbye my sweetheart; we’ll meet Monday at 6 o’clock at the tower.

Kisses from your

Johonzel

From Mileva Einstein-Maric

Budapest, 27 August 1903

Dear Jonzerl,

I’m already in Budapest, it’s going quickly, but it’s hard, I don’t feel at all well. What are you doing, little Jonzile, write me soon, will you.

Your poor Schno[xl?]

To Mileva Einstein-Maric Bern

Friday [19? September 1903]

Dear Schnoxl,

I’m not at all angry that my poor Schnoxl must be on the nest. What’s more, I am even delighted about it and have already been pondering whether I should not see to it that you get a new Lieserl, so that you won’t be deprived of that which is every woman’s right. Don’t worry but come home in a happy mood, and brood very carefully so that something good will hatch out.

I am very sorry about what happened with Lieserl. Scarlet fever often leaves some lasting trace behind. If only everything passes well. How is Lieserl registered? We must take great care, lest difficulties arise for the child in the future.

Now come back to me soon. [Three-and-a-half] weeks have already passed, and a good little wife should not be away from her man for longer than that. But our place still does not look nearly as terrible as you might think. You will quickly put it in order again.

I am getting along with Haller better than ever before. He is quite friendly, and recently, when a patent agent protested against my finding, citing even a decision of the German patent office in support of his complaint, he took my side on all points. You’ll see, I’ll get ahead, so we’ll not have to starve. If only my mother could get a job in Berlin, then we would be out of the woods. It also seems quite certain that Oberlin, who is well disposed toward me, will become a deputy administrator. Luigi will shortly be in Hechingen. It remains to be seen whether he will also come to Bern.

Come soon. Love and kisses from

Jonzl

Cordial greetings to everyone.

To Mileva Einstein-Maric

[Kandersteg] Monday [25 July 1904]

Dear Wife: I saw the dark-blue Blausee in marvelous weather, and now we arrived here in Kandersteg under cloudless skies. My love

To Mileva Einstein-Marie Bern,

Good Friday [17 April 1908]

Dear Sweetheart: I’ve just come home from a long walk with Laub. I work with him a great deal. Unless I am totally mistaken, Minkowski’s determination of ponderomotive forces is wrong. We now derive the whole thing in another way. Nowadays I always take my meals with Laub. We no longer eat at Münze because we both had indigestion — probably because of the questionable fat they use there. I’ve been getting a letter from little Habicht at least every other day, but I don’t always get around to answering him.

I don’t like the solitude at all, Laub notwithstanding. I wait longingly for your return. I ordered two books, O. E. Meyer’s Kinetische Theorie der Gase, and Meisterstücke des Humors, a collection of the best classics in this genre. I haven’t yet talked with Mrs. Hausmann. Pfedi has asked for your address. I was invited to Schenk’s yesterday. He is now courting me a little because . . . Nothing beats selflessness. A capable man is working in Würzburg on my method for the determination of [missing]. I am writing higgledy-piggledy, but what does it matter? Maybe in this way I’ll bring it about that you’ll more willingly let me read your letters.

The apartment is very dirty now — I must prepare you for that. Laub is quite a nice man, though very ambitious, almost rapacious. But he is doing these calculations, which I wouldn’t find time to do, and this is good. He also wants to work on confirming the light quanta.

Kisses to you and Bu from dear

Ba

Convey my cordial greetings to Auntie, Grandpa, Grandma, and Auntie Watz, and also Uncle, if he is there

From Mileva Einstein-Maric

[Prague, 4 October 1911]

Dear Babu, I was delighted with your letter, a few things were missing, though, but hopefully they may still come? It must have been very interesting in Karlsruhe; I would have loved only too well to have listened a little, and to have seen all those fine people. Is the Marx family large, did you do your duty a little bit? It’s been an eternity since we have seen each other, will you still recognize me? Should I really come to Zurich? The weather here is wonderful. Splendid fall weather, wonderful, do we still want to try to do something? Assuming I come, where should I write to inform you about my arrival, for you will pick me up, I hope. For today, many tender feelings from your old

D[oxerl]

To Mileva Einstein-Maric

[Berlin,] 2 April 1914

Dear Mama, I’ve been here in Berlin (Wilmersdorfer St.) since Sunday. It was extremely pleasant at the Ehrenfests. They would like to spend a few weeks together with us in Switzerland if possible. I’m now on familiar terms with Ehrenfest.

It’s nice here. Yesterday I was at Haber’s for the first time; he sends all of you his greetings. I haven’t seen Mrs. Haber yet. Tomorrow I’m going to be at Koppel’s. He gave me a beautiful grandfather’s clock as a welcoming present. Gorgeously mild weather has set in here now; I hope it’s the same for you and that our Tete has no more little earaches, so that he can go outside a lot. Please write me immediately where the money has been deposited so that I can pay the moving expenses. According to a letter by Maag I can do no more in the Gentner affair regarding the heating because I paid the first bill without objection. For God’s sake! Another old tax bill arrived from Prague for about 80 kr. which I must pay. The new landlord is very decent. He’s having everything renovated nicely. The furniture will come on Monday but must be stacked up provisionally in the dining room because the apartment repairs will take another one and a half weeks.

Wishing you all enjoyable holidays and a good rest, yours,

Papa

To Mileva Einstein-Maric, Hans Albert and Eduard Einstein

[Berlin, 10 April 1914]

My Dears,

The director was quite sympathetic. He is very much to my liking. It will be better there than I thought. Lutheran religious instruction. Haber invites you all until the apartment is settled. Happy Easter wishes from your

Papa

Memorandum to Mileva Einstein-Maric, with Comments

[Berlin, ca. 18 July 1914]

Conditions

A. You make sure

1) that my clothes and laundry are kept in good order and repair

2) that I receive my three meals regularly in my room

3) That my bedroom and office are always kept neat, in particular, that the desk is available to me alone.

B. You renounce all personal relations with me as far as maintaining them is not absolutely required for social reasons. Specifically, you do without

1) my sitting at home with you

2) my going out or traveling together with you.

C. In your relations with me you commit yourself explicitly to adhering to the following points

1) You are neither to expect intimacy from me nor to reproach me in any way.

2) You must desist immediately from addressing me if I request it.

3) You must leave my bedroom or office immediately without protest if I so request.

D. You commit yourself not to disparage me either in word or in deed in front of my children. I am ash[amed] for you because you let yourself be so affected by Berlin. Little boy, I only have to say, then he does it right away. Go your own way, let yourself be deceived. I really don’t care. Read this slowly. It will do you good. Read it also to your family, they have nothing else to do.

Ever since coming to Berlin you have become quite lazy. M[ileva] You must also write that thing about Mrs. Haber. They should also know that other people also are interested in how the famous man behaves. Nasty jokes.

To Mileva Einstein-Maric

[Berlin, ca. 18 July 1914]

D[ear] Miza,

Yesterday Haber gave me your letter, from which I gather that you want to accept my conditions. And yet I must write you again so that you are completely clear about the situation. I’m prepared to return to our apartment, because I don’t want to lose the children and because I don’t want them to lose me, and for this reason alone. After all that has happened, a comradely relationship with you is out of the question. It should become a loyal business relationship; the personal aspects must be reduced to a tiny remnant. In return, however, I assure you of proper comportment on my part, such as I would exercise toward any woman as a stranger. My confidence in you suffices for this, but only for this. If it is impossible for you to continue living together on this basis, I shall resign myself to the necessity of a separation.

Requesting a clear reply to this, yours,

Albert

To Mileva Einstein-Maric

[Berlin, ca. 18 July 1914]

D[ear] Miza,

Yesterday Mr. Haber sent for me and advised me to add another comment to you regarding my letter, because I had said in it that what remains of my confidence in you is just enough for a business relationship. It remains possible that I’ll regain a greater degree of confidence in you through proper behavior on your part.

Mileva’s tombstone at the Nordheim Cemetery in Zurich | Tesla Society and Serbia Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Let it be as he wishes. No one can see into the future. In any case, I don’t consider discussions about it useful. Therefore I ask you again whether you want to live with me under the specified terms. Consider it and give me a clear answer with no ifs or buts so that I know where I stand. Kisses to my dear boys,

Albert Einstein

To Elsa Einstein

[Berlin] Sunday. [26 July 1914]

Dear Else,

Today I’m already writing you the first letter, dear one, to make up for the briefness of the farewells. There is already something eminently important to report. My wife requested from Haber a final meeting with me before her departure. On this occasion we determined that Miza is to remain in Zurich with both children, and all the conditions down to the specifics were laid down in writing. It lasted three hours. The way to a divorce has also been smoothed. Now you have proof that I can make a sacrifice for you. What you have suffered in the last few days has made such an impression on me that I couldn’t act in any other way, despite the children.

Although Haber had rather discouraged than encouraged me, I do believe that he does secretly agree with me after all. I must admit that I feel a bit crushed; do you understand? Some time will have to elapse before I am again calmly in possession of myself. Such an affair is bit similar to a murder! But I came to realize that living together with the children is no blessing if the woman stands in the way. Tomorrow they will probably leave; I hope I’ll be able to see my boys one more time!

After the meeting at Haber’s, I drove to your parents, who didn’t come home until after 11 o’clock, though, and received the news not without a mild distaste.

Tonight I’m sleeping in your bed! It is peculiar how confusedly sentimental one is. It is just a bed like any other, as though you had not yet ever slept in it. And yet I find it comforting that I may lay myself in it, somewhat like a tender confidence.

Dear little Else, have a good rest with your children and write me soon. You will help me gradually to regain my composure and confidence after the serious operation. It is really good that you are not here at the moment, because otherwise the severity of the situation would hit you very hard. For the present I cannot think of visiting you, for fear of damaging your good reputation again. Also, in the next few weeks my company is not conducive to summertime recreation. I shall attempt to overcome these difficult first weeks by working busily.

Kisses from your

Albert

Best regards to Ilse and Margot

To Mileva Einstein-Maric [Berlin,]

12 December 1914

D[ear] M[ileva],

I notice just now that I have paid fully for the move. But the tips to the people ought to have been paid by you and, if applicable, the storage fee for Zurich during the waiting period, and the customs charge. I request that you examine the mover’s bill. Should anything more have been paid, I shall claim it back.

I declare to you herewith that I will send you 5,600 M annually in quarterly installments to support you and the children, at least as long as my income does not sink substantially below the present level.

Best regards to Albert and Tete. As long as Albert does not answer my letter I must assume that it has not been given to him. Otherwise I would write to him again.

A. Einstein

To Mileva Einstein-Maric

[Berlin,] 12 January 1915

D[ear] M[ileva],

Officially you are my wife, the same as before, and as such have together with the children a claim to my bit of monetary holdings. But I am not inclined to relinquish the Fr 10,000 which constitute the remains of a sum allotted to me personally for my achievements. I find such a demand beyond discussion. If the share of your paternal inheritance had remained in your parents’ hands, it would have suffered just as much from the war as in your hands. As long as I live, the money in my possession will serve exclusively as security for you and the children, and when I die it will be transferred automatically to the children. The upkeep of all of you has been generously provided for, and I find your constant attempts to lay hold of everything that is in my possession absolutely disgraceful. Had I known you 12 years ago as I know you now, I would have considered my responsibilities toward you at that time quite differently.

A package of returned items, which arrived through no intention of mine in my hands rather than yours, will be delivered to you sometime.

I will maintain a regular correspondence with Albert only if I can indulge in the hope that this is beneficial and pleasurable to the boy. Part of this involves that no pressures be exerted on the child aimed at giving him a distorted image of me. If it is your honest wish not to destroy the personal relations between me and the boys, you will accept the following advice. Read what I write to the children but do not discuss it with them; and above all, let little Albert write to me by himself, do not read his letters, do not admonish him to write me, and do not discuss with him what he ought to write me. In this way you could be sure that I am making no attempts to take the children away from you, and I could be more to the boys than their breadwinner. If I see, however, that Albert’s letters are prompted, then I shall refrain from sustaining a regular correspondence out of consideration for the children.

With best wishes for 1915,

Albert Einstein.