Aisha bursts into the classroom, eyes wide with excitement and worry. “Teacher, have you heard about the massive hurricane crossing the Atlantic? It’s supposed to be a monster!” The class erupts in a flurry of questions and concerns. The teacher, with a calm demeanor, begins to explain. “Yes, these powerful storms are indeed frightening. But did you know that there’s a larger, often unseen force that can influence where and how these storms form?”

This natural process is called the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, or ENSO. It’s a complex interplay between the Pacific Ocean and the atmosphere that can significantly impact weather patterns around the globe. From the most intense hurricanes to the longest-lasting droughts, ENSO can profoundly affect our lives. Let’s dig deeper into this oceanic phenomenon and discover its influence on our world.

The Ocean’s Thermostat

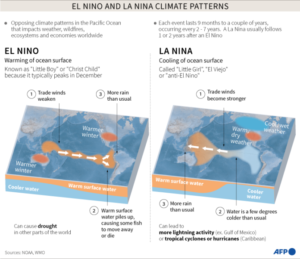

The ENSO is a natural climatic phenomenon that occurs in the tropical Pacific Ocean, the largest oceanic body on Earth. Sometimes the water is warmer than usual in one part, and sometimes it’s cooler. This changing temperature messes with the air above it, and that’s what causes changes in our weather. It has three distinct phases: El Niño, La Niña, and Neutral.

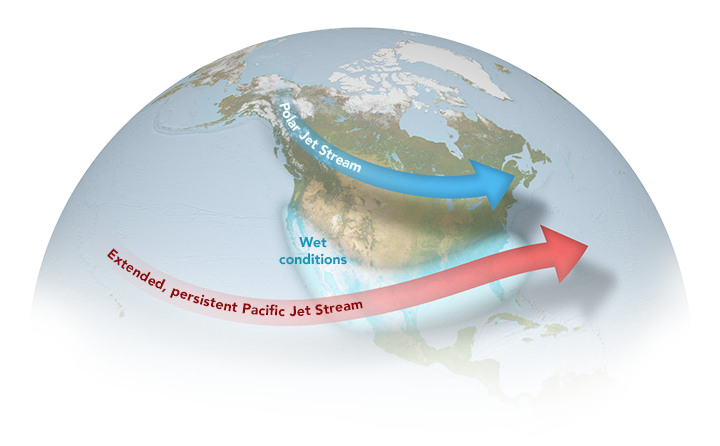

Under normal conditions, when there is neither El Niño nor La Niña, the trade winds (named for their important role in assisting ships with navigation and trade routes) remain stable and consistent over the Pacific Ocean. These winds blow from east to west across the equator, effectively pushing the warm surface layer of water from South America towards Southeast Asia and Australia.

El Niño (Spanish for “little boy”) happens when the eastern waters of the Pacific Ocean become abnormally warm. This warming causes the easterly winds to weaken, then permits warm water to gather in the east. As a result, there is a shift in both ocean temperature and wind patterns, which in turn impacts the atmospheric pressure and influences weather patterns worldwide. In general, countries in the west tend to experience drier conditions, whereas eastern areas like South America observe an increase in rainfall.

La Niña (Spanish for “little girl”) is the opposite of El Niño. The eastern Pacific Ocean experiences cooler-than-average sea surface temperatures. This cooling intensifies the easterly winds, pushing warm water westward. As warm water is displaced, cold water rises from the ocean depths to replace it. This cold water cools the air above, reducing cloud formation and rainfall in the central and eastern Pacific. Consequently, regions in the west, like Australia and Indonesia, often experience increased rainfall, while areas in the east might face drier conditions.

ENSO’s Impact on the Eastern Pacific

El Niño events have the effect of causing sea surface temperatures to rise above average in the eastern Pacific region. As a result, there is an increase in the levels of rainfall and a higher likelihood of more frequent and intense storms. Coastal areas, including California, Oregon, and Washington in the United States, as well as parts of Mexico and Central America, are particularly vulnerable to flooding, erosion, and landslides.

Major cities such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle may experience heavy rainfall and face a greater risk of mudslides. Additionally, the warmer ocean temperatures can contribute to the formation of stronger hurricanes in the Pacific, which can impact regions such as Hawaii and the Pacific coast of Mexico.

Conversely, La Niña conditions bring cooler sea surface temperatures to the Eastern Pacific. This typically results in drier conditions, increasing the risk of droughts, wildfires, and reduced agricultural yields. Regions like Southern California and parts of Mexico may experience water shortages and heatwaves.

ENSO also influences hurricane activity in the Atlantic. The likelihood of a North Atlantic hurricane making landfall in the Continental United States is greater when La Niña conditions are present due to wind shear being reduced. This means that the barrier that would normally inhibit the development of hurricanes is removed.

Unfortunately, this is not good news for people living in areas prone to hurricanes like Florida. In 2020, during the last La Niña event, the Atlantic Ocean experienced an unusually high number of 30 tropical storms and 14 hurricanes. Similarly, in 2021, there were 21 tropical storms and seven hurricanes.

Impacts of ENSO on the Western Pacific

The Western Pacific experiences contrasting weather patterns under ENSO’s influence compared to the Eastern Pacific.

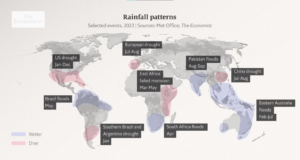

El Niño often brings drier conditions to Australia and Indonesia, leading to droughts, wildfires, and reduced crop yields. However, parts of Southeast Asia may experience increased rainfall. In contrast, La Niña typically increases rainfall in the region, often resulting in floods and landslides in countries like Australia, Indonesia, and the Philippines.

Historical data underscores the severity of these impacts. The 2015-2016 El Niño caused a devastating drought in Ethiopia, affecting millions. The 1997-1998 El Niño led to global damages of £77 billion and triggered a deadly Rift Valley fever outbreak in Kenya.

During La Niña years, the movement of the subtropical ridge towards the west across the western Pacific Ocean increases the likelihood of tropical cyclones making landfall in China. In March 2008, the presence of La Niña caused a drop in sea surface temperatures by 2°C (3.6°F) in Southeast Asia. Consequently, this led to significant rainfall in the Philippines, Indonesia, and Malaysia.

Pakistan’s Weather Rollercoaster

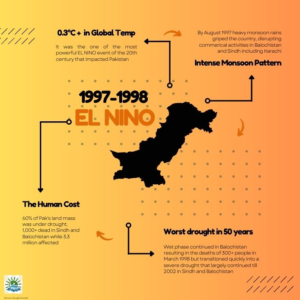

Pakistan is particularly vulnerable to ENSO’s impacts due to its reliance on the Indian monsoon. El Niño weakens the monsoon, leading to droughts, reduced agricultural yields, and water scarcity. Conversely, La Niña intensifies the monsoon, increasing the risk of floods.

In Pakistan, the 1998 El Niño brought heavy snowfall followed by a four-year drought, while the 2009 El Niño preceded the devastating 2010 floods.

El Niño also contributes to rising temperatures, exacerbating heatwaves in Pakistan. This, combined with its potential to disrupt glacial melt in the Himalayas, impacts water availability, hydropower generation, and agriculture.

Understanding these complex relationships is crucial for developing effective adaptation and mitigation strategies in the region.

La Niña on the Horizon

Currently, the world is experiencing a neutral phase of the ENSO cycle. This means that neither El Niño nor La Niña conditions are present, and ocean temperatures in the tropical Pacific are relatively normal.

However, experts predict a shift towards La Niña conditions soon. The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has forecast a 70 percent chance of La Niña developing between now and October. While El Niño events tend to be shorter-lived, La Niña conditions can persist for two years or longer. The ENSO cycle typically oscillates between extreme phases every three to seven years, but the exact duration of each phase can vary.

ENSO and Climate Change

Since May 2024, the world has witnessed an unprecedented phenomenon of twelve consecutive months of record-breaking global temperatures. The ocean, which retains exceptionally high temperatures, is the primary contributor to this extraordinary warmth.

The recent El Niño event was strongest and significantly contributed to the record-breaking temperatures. While scientists are still investigating the exact relationship between climate change and ENSO, it is evident that the conditions are being amplified and becoming unpredictable. Close monitoring of these systems is crucial for understanding future climate patterns and developing effective adaptation strategies.

According to Prof Dr Jin-Yi Yue, weather phenomena happening in the 21st century differ from what was observed in the previous century. It’s as if the “Little Boy” is evolving. This could explain why weather models, which accurately predicted events such as the powerful El Nino in 1997/98, have struggled to do so in the 21st century.

Conclusion:

The interplay between ENSO and climate change is reshaping our planet’s weather patterns in unprecedented ways. As we navigate this new era of climate extremes, it’s clear that understanding these complex interactions is paramount. While the challenges are massive, so are the opportunities for innovation and adaptation. We can build a more resilient future by investing in research, developing early warning systems, and implementing sustainable practices. Our choices today will determine the world we leave for generations to come.

References:

- “Impacts of El Niño and La Niña on the hurricane season” – Climate.gov

https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/impacts-el-nino-and-la-nina-hurricane-season

- “La Niña is coming. Here’s how it could change the weather.” – The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/weather/2024/07/11/la-nina-el-nino-weather-impacts-cooling/

- Doane‐Solomon, R., Befort, D. J., Camp, J., Hodges, K., & Weisheimer, A. (2024). The link between North Atlantic tropical cyclones and ENSO in seasonal forecasts. Atmospheric Science Letters, 25(1), e1190.

- “Exploring the Complexity of El Nino and its Effects on Rainfall in Pakistan” – Pakistan Weather Portal. https://pakistanweatherportal.com/2023/04/30/exploring-the-complexity-of-el-nino-and-its-effects-on-rainfall-in-pakistan/

- “2024 Pacific Tropical Cyclone Outlook: Transition To La Niña” – Pole Star. https://www.polestarglobal.com/resources/2024-pacific-tropical-cyclone-outlook-transition-to-la-nina

- https://www.weather.gov/jan/el_nino_and_la_nina

More from the author: Cooling Karachi — Combating Urban Heat with Green Spaces

Aly Muhammad Gajani holds a Master’s degree in Space Science and Technology, specializing in Astrophysics together with GIS applications. His research focuses on galaxy evolution, astrophysical cosmology, exoplanet detection, and computational astronomy.