Imagine sitting at your favorite restaurant, your food served, and taking a bite of a crispy, fried chicken piece. Hot, juicy, and delicious. You don’t question it; you shouldn’t. But suppose that every piece of chicken had something more than spices and protein attached to it. What if it had residues of antibiotics, untouched and unaffected by cooking? What if that meal progressively caused you to become resistant to life-saving drugs? This is the untold story of how antibiotics have changed the way we grow chickens, and how, if we don’t act now, they could transform the future of medicine in ways none of us want.

Why Do Farmers Use Antibiotics?

Chicken is everywhere. It’s on our plates, in our packed lunches, at weddings, and even on the street corner, sizzling away in roadside stalls. And it’s not uncommon for poultry production to have tripled in the last few decades. Farmers around the world are forced to produce more, quicker, and cheaper yields, and one of their most trusted shortcuts is Antibiotics.

Originally introduced to treat disease, antibiotics then found another job: making chickens grow faster. These are known as antibiotic growth promoters (AGPs). To satisfy increasing demand, farmers give chickens small amounts of antibiotics in their feed not to help them recover from illness, but to speed up growth and minimize the threats of disease. Such usage gives chickens more weight per pound, shorter life cycles, and eventually more meat to meet consumer preferences.

The Invisible Ingredient in Your Chicken: Antibiotics

Most people think that cooking destroys all that is bad. Heat kills bacteria, right? It’s easy to assume that cooking would take care of any antibiotics in meat, but is that really the case? Not exactly.

Research shows that the amount of antibiotic residues in meat can be minimized by cooking, boiling, roasting, grilling, or microwaving. A recent Egyptian study, conducted by Kamouh et al. (2024), detected residues of OTC, gentamycin, and oxytetracycline in retail chicken. The study reported that boiling for 30 minutes reduced OTC and gentamycin levels by 88-95% while ciprofloxacin levels dropped by 31%.

So, that perfectly grilled chicken leg? It may still carry tiny leftovers of antibiotics. Not enough to make you sick immediately, but enough to slowly mess with your gut health or worse, train bacteria in your body to resist future medications.

The Slow and Silent Rise of Antibiotic Resistance

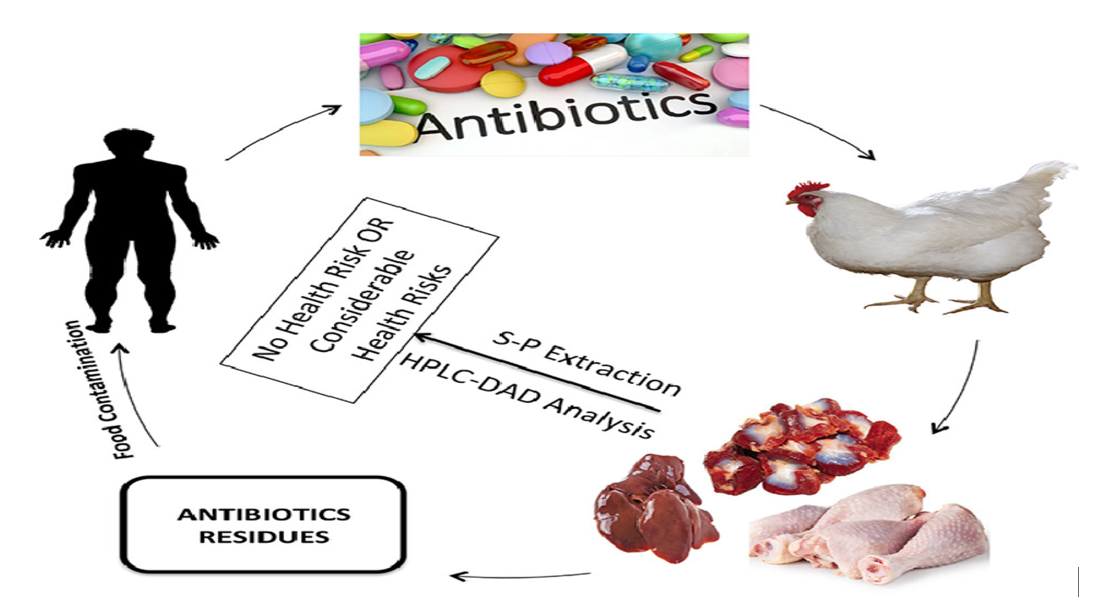

Resistance doesn’t appear overnight; it develops gradually, step by step, through ongoing exposure to small doses of antibiotics in our food. It’s not a single meal or single mistake; it’s a process. Let’s trace the path from chicken feed to antibiotic resistance.

It all starts at the farm, where a farmer gives chickens low-dose antibiotics in feed, which might seem harmless or even helpful. But inside chickens, not all bacteria are killed. Some of them survive, adapt, and become stronger. These bacteria learn to survive the antibiotics and slowly evolve into drug-resistant strains. These resistant bacteria and antibiotic residues stay in the meat.

The meat is processed, cooked, and eaten; these resistant bacteria, on entering the gut, transfer their resistance genes to the natural bacteria. The next time you get sick, the infection might not respond to antibiotics. It is because the bacteria have already been exposed to the antibiotic, and they have developed resistance to it.

This is not a hypothetical concern; evidence from multiple studies highlights the presence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, including E. coli and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), in chicken meat, farm environments, and even among individuals with no direct contact with livestock, indicating the food chain as a significant route of transmission.

Global Action on Antibiotic Use: Progress Made, Gaps Remaining

Some developed countries, including Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and the European Union, have taken bold steps and banned the use of antibiotics as growth promoters, resulting in a noticeable drop in resistant bacteria both on farms and in the food. But in most regions of the world, the application of antibiotics in chicken farming remains uncontrolled. In some areas, including Pakistan, antibiotics essential for human medicine are used freely in animals. Regulatory policies exist on paper but are poorly enforced, and short-term profits are prioritized over long-term public health.

These practices have raised concerns about animal welfare, health problems in oversized birds, and questions about meat quality.

What Can Be Done and What You Can Do?

The solution to this problem is not giving up chicken. This chicken–antibiotic–antimicrobial resistance triad crisis can be solved by demanding better and smarter practices. What can actually be done?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) aims to involve veterinarians at every stage of antibiotic usage while discouraging reliance. Farm hygiene and animal health must also be improved to limit the use of antibiotics. The World Health Organization takes it further, making a bold stance:

In line with this, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) says that farmers need to be trained to follow withdrawal periods— the time it takes for antibiotics to fully leave a chicken’s system before it’s processed for food. Organizations such as ICARS urge the investigation of alternatives to antibiotics, like prebiotics, and natural antimicrobial substances, promising a brighter future in which dependency on repeated antibiotic use is not the norm.

You, as a consumer, also have power. Stand behind poultry brands that adhere to safe and sustainable practices. Ask questions. Make informed choices. Because it’s not just a farm problem—it’s a kitchen table problem.

The same medications that healed millions last century are gradually losing their strength, and one of the major contributors is the chicken on our plates. But awareness is the first step to action. The next time you have chicken for dinner, “Pause”. Not to feel guilty but to feel enlightened; beneath the flavors is a tale, a tale of science, farming, resistance, and the opportunity to alter direction before it’s too late.

References:

- Muaz, K., Riaz, M., Akhtar, S., Park, S., & Ismail, A. (2018). Antibiotic Residues in Chicken Meat: Global Prevalence, Threats, and Decontamination Strategies: A Review. Journal of Food Protection, 81(4), 619–627. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-17-086

- Fey, P. D., Safranek, T. J., Rupp, M. E., Dunne, E. F., Ribot, E., Iwen, P. C., Bradford, P. A., Angulo, F. J., & Hinrichs, S. H. (2000). Ceftriaxone-resistant Salmonella infection acquired by a child from cattle. The New England journal of medicine, 342(17), 1242–1249. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200004273421703

- Levy, S. B., FitzGerald, G. B., & Macone, A. B. (1976). Changes in intestinal flora of farm personnel after introduction of a tetracycline-supplemented feed on a farm. The New England journal of medicine, 295(11), 583–588. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM197609092951103

- Kamouh, H. M., Abdallah, R., Kirrella, G. A., Mostafa, N. Y., & Shafik, S. (2024). Assessment of antibiotic residues in chicken meat. Open Veterinary Journal, 14(1), 438–448. https://doi.org/10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i1.40

- (Aarestrup, Frank Moller, et al.; Bager, Flemming, et al.)

Similar Articles: Antibiotic resistance: A war against an invisible pandemic

Love-Hate Relationship between the Gut Microbiota and the Brain

Hadia Rashid is a BS (Hons.) student of Applied Microbiology at UVAS Lahore. Passionate about science communication, she writes to bridge the gap between research, the environment, and society.