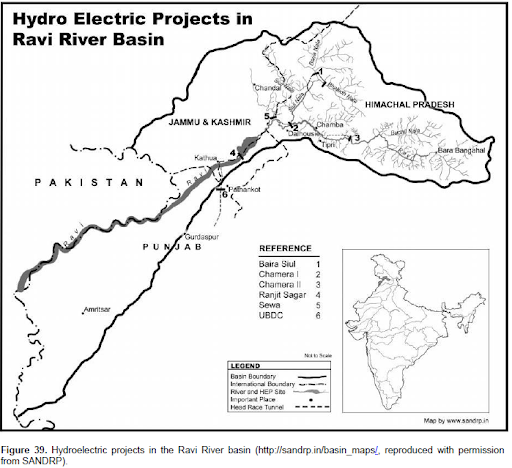

One of the five rivers for which Punjab was named of the Ravi River, which flows from northwest India to northeast Pakistan, flows from the Himalayas in Himachal Pradesh, India, passing Chamba, turning to Jammu & Kashmir, and then entering Pakistan. It flows 50 miles before entering the Punjab province of Pakistan. It flows from Lahore to Kammalia, entering the Chenab River.

The Indus Waters Treaty (1960), which authorized India to use the waters of the Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej, is linked to the Ravi’s fall over time. After that, dams and barrages changed their course, making it flow like a stream that only flows during the monsoon season in Pakistan. Over time, the main source of water for the river was limited to cities, especially around Lahore. [1]

Hydrological estimations indicate that before the mid-20th century, the Ravi’s floodplain in Punjab reached several kilometers on both banks, sustaining seasonal wetlands and riparian trees. These places were essential for migratory birds, renewing soil fertility and recharging aquifers.

In 2024, India blocked the flow of the River Ravi into Pakistan in a premeditated maneuver that was both astonishing and unexpected. This might be a death sentence for Lahore and other adjacent towns in terms of water needs, as the recently constructed Shahpur Kandi dam permits India to retain 1,150 cusecs of water that was previously destined for Pakistan. The data also shows that the dam began rerouting 1,150 cusecs of water to irrigate around 32,000 acres in the districts of Samba and Kathua in Occupied Jammu. [2]

Importance of the Ravi Riverbanks and Wetlands

Over the decades, rapid and unregulated urbanization caused the degradation of the Ravi. The environment, and contamination of its banks, as this critical water body is the recipient of untreated water, the site of commercial sand mining, deforestation, and ad hoc land use conversions. [3]

River Ravi’s wetlands and riverbanks were essential for several factors, such as biodiversity, groundwater recharge, soil fertility, climatic regulation, ecological balance, and local livelihoods. These functions have been hampered by their deterioration over time as a result of decreased flows, urbanization, and pollution.

According to WWF-Pakistan, there used to be roughly 38 different kinds of fish in the Ravi between Lahore and Head Sidhnai, but virtually all died due to contaminated water, very little dissolved oxygen, and sewage that hasn’t been cleaned. A study conducted by Punjab University found that more than half of the species that used to live in the river are either fewer in number or have completely disappeared. The loss of these species makes the river’s ecosystem even more unstable, which makes it harder to bring the river back to its natural state. [4]

Until 2022, the flows in the Ravi at Ravi Syphon decreased from a peak of 920,000 to just 63,720 cusecs. The upstream infrastructure has slowly grown watertight, preventing any downstream leakage, except during the 1988 high floods. In one instance, Ravi’s high floods at Jassar in 1955 were 680,000 cusecs, whereas in 2023 they were only 71,010 cusecs. [5]

The Role of Land Conversion and Encroachment in Ravi’s Degradation

The launch of the Ravi Urban Development Authority (RUDA) in 2020 further accelerated plans to build a “new city” along a 46-km stretch, marketed as sustainable but criticized for threatening riparian ecology and farming.

Illegal colonies, factories, and building projects have taken over large areas of the riverbanks along the Ravi River as cities grow. The Punjab Urban Planning and Development Authority did a survey and found that around 30% of the river’s banks have been built on in the last 20 years.

These encroachments not only block the river’s natural flow, but they also raise the risk of flooding during the monsoon season. As towns grow and infrastructure projects go on, the loss of important riparian zones and wetlands along the Ravi River is a big threat to both the river and the people who live nearby. [4]

In July 2020, an Act of the Punjab Assembly established RUDA as a government agency. It is in charge of the Ravi Riverfront Urban Development Project, also referred to as Ravi City, which spans around 46 kilometers along the Ravi River.

The goals of RUDA include turning the Ravi back into a perennial freshwater river, building contemporary residential and commercial areas (such as Chahar Bagh, Sapphire Bay, Souq District, etc.), establishing green belts, planting six million trees, water treatment facilities, flood control infrastructure, eco-industrial zones, and themed industries (such as medical, educational, and industrial). [6]

Several housing societies have sought and been granted permission by RUDA to develop their properties. These societies have been divided into groups according to the kinds of RUDA licenses they have obtained, including Final Sanctions, Technical Approval for Land Subdivisions, and Provisional Planning Permission (PPP).

Seven housing schemes have received RUDA approval with provisional planning authorization, six have received technical approval, and final approval verifies that the housing schemes satisfy all official, legal, and technical requirements, of which there are just two. [7]

The Ravi’s Return: Impact of Ravi’s Reclamation

On 26th August National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) issued a significant flood warning for the river Ravi as “This intense rainfall, combined with the downstream flows from the Madhupur Headwork (subject to releases), is expected to result in VERY HIGH TO EXCEPTIONALLY HIGH FLOOD LEVEL at JASSAR, SHAHDARA & BALLOKI during the next 48 hours.” According to NDMA from 26th June to 7th September, 910 deceased and 1044 injured, of which 234 are dead from Punjab and 654 are injured. [8]

The effects on agriculture were severe: low-lying, productive fields around Lahore, Sheikhupura, and Kasur that were grown without floods saw crop losses due to standing water, which harmed maize and rice harvests and reduced the fertility of the topsoil. The consequences of large-scale projects like the Ravi Urban Development Authority (RUDA), which has been constructing residential and commercial zones along a 46-km river corridor, were also evident due to the submerged roads, industrial sites, and encroached colonies [6].

In addition to the immediate harm, the ecological repercussions include soil instability, contamination from floodwater and urban sewage, and the loss of the last riparian vegetation that absorbed excess water and prevented erosion. Reclaiming floodplains is a natural river process that becomes disastrous when human development disregards hydrological reality, as Politico observed, affecting over 2 million people in Punjab. [9]

In 2025, unprecedented floods on the Ravi reversed decades of reclamation, with flows exceeding 215,000 cusecs at Shahdara, inundating low-lying urban settlements and destroying crops across Punjab, displacing thousands of families and exposing the risks of building on riverbeds.

This cycle shows how human occupation of floodplains, while offering short-term urban expansion, has deepened long-term vulnerability to ecological disaster and agricultural loss. Ravi’s reclamation during the 2025 floods demonstrates how building on dried riverbeds creates false security. When rivers reclaim their space, the consequences are amplified: flooding destroys agriculture, displaces urban populations, and erodes ecological resilience.

References:

- https://www.britannica.com/place/Ravi-River.

- https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/1184047-water-politics?utm.

- “Rivers, Cities and People: Social Challenges of Urban Waterfront Development,” 2025.

- “Earth5R, https://earth5r.org/. A. T. Sheikh, “The eastern rivers,” DAWN, 2023.

- “Ravi Urban Development Authority, Government of the Punjab,” [Online]. Available: https://ruda.gov.pk/about.

- “NDMA,” [Online]. Available: https://ndma.gov.pk/sitrepm.

- Seven housing schemes have received RUDA approval with provisional planning authorization, six have received technical approval, and final approval verifies that the housing schemes satisfy all official, legal, and technical requirements—of which there are..

- https://www.politico.com/

Also, Read: Breaking the Cycle: Community Resilience is Key to Addressing Pakistan’s Ongoing Flood Crises

Zunaira Noor is an alumna of the University of Sargodha. She’s passionate about science, especially climate change, biodiversity, and genetics. In her free time, she enjoys fabric painting and exploring the intersection of art and science.