Hundreds died, a rescue helicopter crashed, villages submerged, families torn apart, weddings turned to funerals. These are news headlines you must have heard. But have you thought about why this all happened? We ignored nature warnings for so long, and now Pakistan is facing a climate-driven disaster.

From North to South, a surge in natural disasters has been experienced. Cloud bursts, flash floods, and landslides accompanied this season’s relentless monsoon rains. The scale of human suffering is staggering. Communities left to grapple with loss and livelihoods erased in moments. The overwhelming infrastructure in cities like Karachi and Rawalpindi could not resist the misery of citizens. Climate change is intensifying extreme events that were once rare.

The public and policymakers need to be aware of effective solutions for disaster preparedness and management. Scientia Magazine invites Dr Mujtaba Hassan to discuss the role and implications of space technologies for Pakistan’s unique challenges.

Currently, Dr Mujtaba serves as an Associate Professor at the Department of Space Science, Institute of Space Technology (IST), Islamabad. He is also a Regular Associate of the Earth System Physics Section at the International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP), Italy, and a Research Fellow at the University of Glasgow, Scotland. His major research areas include Climate System Dynamics, Regional Climate Modeling, Climate Variability, Extreme Weather Events, Hydrological Modeling, and Climate Change Impact Assessment on Water Resources.

In this gravity-laden backdrop, we sit with Dr Hassan to discover how Pakistan can harness space technologies to build a safer and more resilient future. Here are snippets of the interview.

Hifz: To begin with, can you share a little about your aspirations and journey to leading the Space Science Department?

Dr Hassan: My journey into science has been shaped by curiosity and a deep interest in understanding the natural world. I began with a Bachelor’s degree in Mathematics and Physics, which provided a foundation to observe natural phenomena through both analytical and physical perspectives.

Building on this, I pursued a Master’s degree in Meteorology from COMSATS University Islamabad. It was during this time, particularly through my exposure to the Pakistan Meteorological Department, that I developed a fascination with atmospheric physics, climate science, and the processes that govern weather and climate systems. That experience became the turning point in defining my academic and professional path.

In 2012, I joined the Institute of Space Technology as a Lecturer in Meteorology. Later that same year, I was accepted into the PhD program at Tsinghua University in China, consistently ranked among the top 15 universities worldwide. Driven by a passion to advance climate science, I moved there on study leave to specialize in climate modeling, extreme events, and their hydrological impacts. I studied at a globally renowned institution, which enhanced my research skills and gave me the confidence to contribute to international discussions on climate change and environmental science.

After completing my PhD in 2016, I returned to IST and resumed my role with a renewed vision for research and teaching. In 2022, I was promoted to Associate Professor and appointed as Head of Department in October 2023.

Now I lead a dynamic department that offers undergraduate programs in Space Science and Physics, as well as advanced Master’s programs in Remote Sensing & GIS, GNSS, and Astrophysics. I also teach courses in atmospheric physics, hydrometeorology, climate system dynamics, and climate change adaptation at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels.

For me, this journey has always been about more than just academic milestones; it has been about inspiring students, advancing scientific knowledge, and connecting research with real-world challenges. I aspire to continue expanding the frontiers of space and climate sciences in Pakistan, equipping the next generation of scientists to address pressing issues of climate resilience, environmental sustainability, and space applications.

Hifz: How would you describe the current state of climate variability in Pakistan? Are we witnessing a shift?

Dr Hassan: The answer is yes. Pakistan is currently experiencing significant climatic changes. These developments represent not merely variability but a fundamental shift in temperature, precipitation, and hydrological patterns.

Over the decades, the country has warmed faster than the global average, and the signs are undeniable. Summers are hotter, heatwaves arrive earlier and stay longer, and temperatures in places like Jacobabad now touch the very limits of human survival. At the same time, rainfall is becoming less predictable but far more destructive. The monsoon is no longer a gentle season; it can now unleash devastating cloudbursts in a matter of hours.

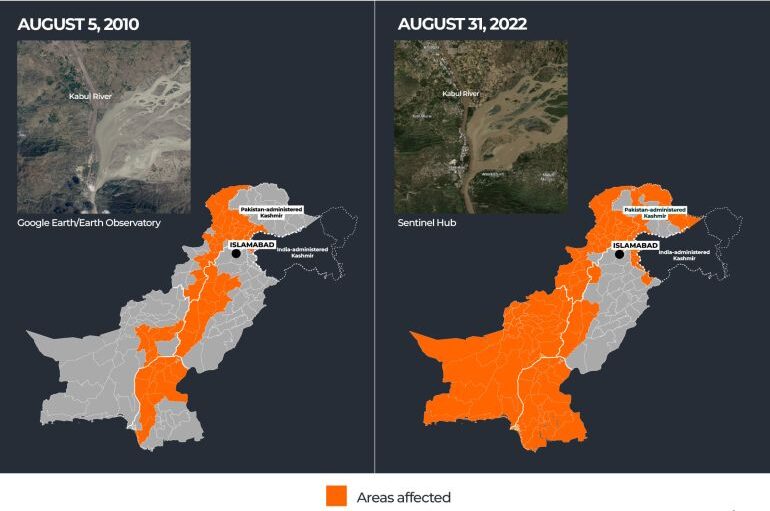

The warning signs have been building for over a decade. In 2010, unprecedented monsoon rains submerged nearly one-fifth of the country, displacing millions and leaving a humanitarian crisis in their wake. Twelve years later, in 2022, another catastrophic monsoon hit, this time bringing rainfall so intense that scientists confirmed climate change had made it far more likely. Those floods killed over 1,700 people and caused damage estimated at $40 billion, making them one of the costliest disasters in Pakistan’s history.

Fast forward to 2025, and the picture is even clearer. In August, cloudbursts and flash floods tore through Buner and Swat in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, claiming more than 300 lives and washing away entire communities. Just weeks earlier, in Gilgit-Baltistan, a Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) had burst through mountain valleys, destroying roads, bridges, and villages. These back-to-back disasters underline a new reality: what once felt like once-in-a-generation events are now recurring with alarming frequency.

In Pakistan’s high mountains, another story is unfolding. While glaciers across the Himalayas and Hindu Kush are retreating rapidly, the Karakoram range has behaved differently. Known as the “Karakoram anomaly,” some glaciers have remained stable or even advanced slightly. But this is not a sign of safety; it is a regional exception caused by unique weather patterns.

Scientists warn that even this anomaly is unlikely to last as global temperatures continue to rise. The melting of our “water towers” will profoundly reshape river flows, agriculture, and hydropower in the coming decades.

So yes, Pakistan is already in the midst of a climatic shift. The baseline is hotter, extremes are more dangerous, and mountain systems are under stress. What were once extraordinary events are now becoming disturbingly common. The challenge ahead is clear: to strengthen early warning systems, redesign infrastructure for extreme situations, and prepare communities for a future that will be hotter, wetter, and less predictable.

Hifz: What have been the most alarming findings regarding climate change effects on Pakistan?

Dr Hassan: Perhaps the most unsettling reality is that Pakistan, despite contributing less than 1 percent to global greenhouse gas emissions, remains among the most climate-vulnerable nations in the world. The evidence emerging from scientific studies paints a stark picture.

We are witnessing a rise in temperature extremes, with heatwaves now arriving earlier, lasting longer, and reaching unprecedented intensities. In recent years, parts of Sindh and southern Punjab have recorded some of the world’s highest temperatures, directly impacting human health, agriculture, and energy demand.

Another alarming signal is the tightening link between climate change and water insecurity. With rainfall variability, reduced snow cover, and changing river flows, Pakistan’s agriculture, the backbone of its economy, faces unprecedented challenges. This, combined with rapid urbanization and population growth, raises serious concerns about food security, public health, and internal migration in the decades ahead.

In short, science tells us that climate change in Pakistan is not a distant scenario. It is unfolding now; in our heatwaves, in our floods, in our glaciers, and in our water cycle. The most alarming finding is not any single event, but rather the accelerating pace at which these multiple risks are converging.

Hifz: Climate change has become a driver of extreme weather events. How can spatial data and predictive models support policymakers and shape climate-resilient infrastructure and planning?

Dr Hassan: Spatial data and predictive models are not just scientific tools; they are decision-making compasses in an era of climate uncertainty. For Pakistan, where floods, heatwaves, and glacial hazards are intensifying, they provide the evidence base needed to design smarter, climate-resilient infrastructure.

High-resolution satellite imagery and GIS-based mapping allow policymakers to visualize risk in space and time. For instance, floodplain maps can identify where river overflows are most likely, helping ensure that settlements, roads, and power plants are built outside high-risk zones. Similarly, glacial monitoring highlights vulnerable valleys in Gilgit-Baltistan, guiding the placement of protective walls, early-warning sirens, and evacuation routes.

Predictive models add a forward-looking lens. By simulating different climate and hydrological scenarios, these models can estimate how a city like Karachi may respond to rising sea levels or how future monsoon shifts could affect dams and irrigation systems. This foresight enables investments in resilient housing, elevated highways, and adaptive irrigation systems that can withstand tomorrow’s climate realities rather than yesterday’s.

Perhaps most importantly, spatial data makes climate science accessible to decision-makers. When a minister can see, on a map, the overlap between poverty hotspots and flood risk zones, the urgency of climate adaptation becomes tangible. It transforms climate resilience from abstract policy into targeted, evidence-driven action.

Integrating spatial data and predictive modeling into planning is Pakistan’s best chance at moving from crisis response to climate resilience.

Hifz: How can the integration of GIS and space technologies transform disaster management in Pakistan?

Dr Hassan: Pakistan is on the frontline of climate hazards, from erratic monsoons and prolonged droughts to flash floods and GLOFs. In this context, GIS and space technologies offer a transformative edge.

Through satellite-based remote sensing, we can monitor rainfall anomalies, snowmelt, and glacier movements in real time. When layered into GIS platforms, this data produces risk maps that highlight flood-prone valleys, vulnerable settlements, and critical infrastructure.

The impact is threefold:

- Early warning – Predicting heavy rainfall or GLOF events with higher accuracy and communicating risks directly to communities.

- Emergency response – Rapid satellite flood-mapping, as seen during the 2022 floods and again in the 2025 Swat and Buner flash floods, helps relief agencies prioritize the hardest-hit areas.

- Long-term resilience – Identifying climate hotspots to guide safer urban planning, resilient agriculture, and climate-adaptive infrastructure.

In essence, integrating GIS with space-based monitoring shifts disaster management from reactive relief to proactive resilience, a critical step as Pakistan faces intensifying climate extremes.

Hifz: Can you elaborate on the functions and benefits of Automatic Weather Stations, Weather Forecasting Models, and Hydrological Forecasting Models in avoiding tragedies?

Dr Hassan: When we talk about extreme weather events in Pakistan, such as flash floods or cloudbursts, the challenge is not just their intensity but also their suddenness. The difference between a tragedy and a near-miss often comes down to minutes or hours of warning. This is where modern forecasting technologies play a transformative role.

Automatic Weather Stations provide the first layer of defense by feeding us real-time information on rainfall, wind, temperature, and atmospheric pressure. This constant flow of data makes it possible to detect rapid changes in local weather systems, the kind of changes that precede a cloudburst. Once this information is captured, forecasting models step in. By assimilating these observations, numerical weather prediction models simulate the atmosphere and give us an early indication of how a storm cell is likely to evolve, where it may intensify, and how quickly it may strike.

But forecasting the rain alone is not enough. The next question is: what happens once that rain hits the ground? Hydrological models help answer this by simulating how rivers, catchments, and glacial lakes will respond to heavy precipitation. In a mountainous region like northern Pakistan, where the risk of flash floods and GLOF events is high, these models are indispensable. They allow us to anticipate the downstream impact of a cloudburst, which valleys may flood, which communities are at risk, and how much time is available to act.

The integration of these systems creates a chain of foresight, turning raw weather data into actionable warnings. We saw during the 2010 super floods, the 2022 climate-induced flooding, and the 2025 flash floods in Buner and Swat, along with the GLOF event in Gilgit-Baltistan, that the cost of weak forecasting capacity is measured in thousands of lives and billions in damages. Strengthening these tools means moving toward a future where Pakistan is not caught off guard by climate extremes, but rather anticipates them with science-driven preparedness.

Hifz: What role do scientific tools play in early warning systems or disaster risk reduction planning in Pakistan?

Dr Hassan: Scientific tools are the backbone of any effective early warning and disaster risk reduction strategy. In a country like Pakistan, where climate extremes are intensifying, their role is not optional; it is essential.

Today, Automatic Weather Stations, satellite-based observations, Doppler radars, and high-resolution forecasting models enable us to track evolving weather systems in real time. For instance, a storm cell forming over the Arabian Sea can be monitored from its inception, its trajectory simulated, and its potential impact zones mapped hours to days in advance. This transforms our approach from reactive to proactive.

Equally important are hydrological and flood forecasting models, which translate rainfall data into real-world impacts. Instead of merely knowing that it will rain heavily in northern Pakistan, these models tell us how rivers like the Swat or Indus will respond, which communities may be inundated, and how much lead time is available for evacuation.

Space technologies further strengthen this chain. Satellites provide near-instantaneous information on cloud formation, glacial melt, soil moisture, and land use, all of which feed into predictive models. This integration has been critical in monitoring high-mountain hazards such as GLOFs, where minutes of warning can mean the difference between safety and catastrophe.

When these tools are embedded into disaster risk reduction planning, they do more than issue warnings; they guide long-term resilience. Governments can identify vulnerable zones, design flood defenses, plan evacuation routes, and even adjust cropping calendars to align with changing climate patterns.

The reality is that technology does not stop disasters from happening, but it does ensure that when nature strikes, Pakistan is informed, prepared, and better positioned to protect lives and livelihoods.

Hifz: What challenges do you face in translating technical geospatial insights into policy-level action? There are certain challenges, like an ignorant public, unsupportive authorities, and a lack of awareness. How can you cope with such challenges in practical scenarios?

Dr Hassan: Translating complex geospatial and climate insights into meaningful policy or community action is never straightforward. The biggest challenge is the communication gap. Scientific models and maps are full of technical variables, probabilities, and uncertainties, while policymakers and communities need clear, actionable messages.

Telling a minister that rainfall intensity will increase by 20 percent often fails to resonate, but showing that this translates into thousands of homes at flood risk immediately changes the conversation.

Another obstacle is the short-term mindset of both authorities and the public. Policy cycles are often focused on immediate political or economic priorities, while communities may underestimate risks that feel distant or abstract. This was evident in the years before the devastating floods of 2010, 2022, and the more recent 2025 events, where early warnings existed, but limited awareness and preparedness magnified the tragedy.

Overcoming these barriers requires a multi-layered approach. For policymakers, we convert technical findings into economic and social terms, highlighting how proactive planning saves billions in recovery costs.

For the public, we invest in awareness campaigns, school programs, and local-language trainings, helping vulnerable communities understand phenomena like cloudbursts or GLOFs in ways that directly relate to their safety and livelihoods.

Persistence and partnerships are equally crucial. Authorities may be unsupportive at first, but consistent engagement, backed by evidence and supported by NGOs, international donors, and local governments, gradually creates a culture of trust.

When science is framed not as abstract data, but as a tool for protecting lives, homes, and futures, resistance gives way to collaboration. The key lies in humanizing science; turning maps into stories, numbers into impacts, and forecasts into community action. Only then can technical insights truly shape resilience on the ground.

Hifz: How do educational institutions help train people for disaster management, as more than the government, people need to learn it?

Dr Hassan: Educational institutions are at the frontline of building a culture of resilience. Governments may set policies, but it is ultimately people, families, communities, and professionals who must understand risks and respond effectively during disasters.

Universities and schools have the responsibility not only to create knowledge but also to translate it into practical skills that save lives. At the Department of Space Science, IST, we place a strong emphasis on training students in atmospheric and climate sciences, disaster risk modeling, and geospatial applications.

Our students learn to analyze real data, run forecasting models, and develop community-centered solutions. Many of my own graduates, whom I had the privilege to supervise during their final-year projects and theses, are now working with the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) and related organizations. Their expertise is directly contributing to early warning systems, climate impact assessments, and risk preparedness strategies at the national level.

Beyond technical training, educational institutions also nurture a mindset of responsibility and awareness. When students understand how a cloudburst can devastate a valley or how mismanaged urban planning worsens flooding, they become advocates for resilience in their own communities. In this way, universities act as both incubators of expertise and multipliers of awareness.

Ultimately, disaster management is not the job of the government alone. It is a shared responsibility, and by equipping young scientists and citizens with knowledge and skills, educational institutions ensure that resilience begins long before the next emergency.

- You Might Also Like: Flooded Again: The Science and Policy Missteps Plaguing Resilience in Swat

- More From The Author: The Dark Side of Climate Change: Crimes, Conflicts and Environmental Destruction