The bus jolted to a stop, waking Hassan abruptly. Stepping off, he was hit with a blast of intense heat from the midday sun, which hung high in the cloudless sky like a relentless white disk. Sweat formed on his forehead despite the cap he loosely held over his head. Hassan squinted at the “park” across the street– a dusty area of cracked earth with a few scraggly trees offering minimal shade.

Supposed to be a refuge from Karachi’s scorching summer, a place to escape the oppressive heat trapped between towering buildings, it was a constant disappointment. Hassan sighed, feeling the familiar disappointment settle in his chest. Surely, there had to be a better way.

Hassan’s story was not unique. Millions of Karachiites faced the harsh reality of urban heat. With limited green spaces and temperatures regularly exceeding 38°C, finding relief from the relentless sun is a daily struggle.

However, what if the solution wasn’t just enduring the heat but actively fighting against it? The answer lies in a solution as simple as nature itself – creating a network of thriving urban green spaces.

Amidst the rising global temperatures, the world is becoming increasingly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. The recent global climate report released by NOAA states that April 2024 was the warmest April ever recorded worldwide, surpassing the previous record set just four years prior. As Pakistan ranks fifth on the list of countries most at risk from climate change (UN-Habitat, 2023), the urgency of addressing these challenges becomes ever more apparent.

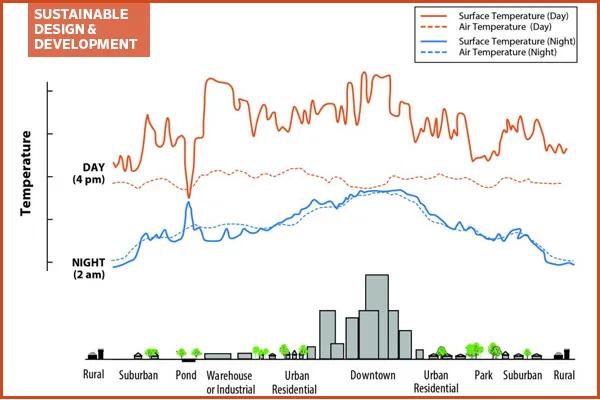

But why does the heat feel so intense in urban areas like Karachi? It’s due to the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect. Buildings, roads, and other infrastructure absorb and release more of the sun’s heat compared to natural landscapes like forests and bodies of water. This is especially true in urban areas where there are many structures and limited greenery, resulting in localized areas of higher temperatures known as “heat islands.”

The lack of green spaces that provide a cooling effect causes urban temperatures to skyrocket, making summers even more unbearable. Studies have shown that surface temperatures in cities can be a staggering 10-15°C higher than in surrounding rural areas (Mentaschi et al., 2022).

Heat Islands—Impact on Quality of Life

The Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect significantly impacts the quality of life in Karachi. It causes heatwaves to last longer in the city, resulting in abnormally hot and often humid weather. This has serious consequences for health, such as heat exhaustion, heatstroke, and even death, particularly among vulnerable groups like children, the elderly, and those with pre-existing health conditions.

A recent project by Aga Khan University seeks to measure extreme heat’s impact on maternal and child health. Researchers are concerned about the greater impact of heat stress and temperature fluctuations on pregnant women. Gynecologist Safia Manzoor from Lyari General Hospital states, “We have noticed an increase in cases of pre-term births during hot weather.”

In addition, high temperatures cause air pollutants, such as smog, to become trapped close to the ground, exacerbating conditions like asthma and other respiratory illnesses. This makes breathing difficult and increases the risk of respiratory attacks. Residents rely more heavily on air conditioners and fans to cope with the heat, resulting in higher electricity bills and straining Karachi’s power grid. This leads to more frequent power outages and energy shortages.

A US-based study has indicated that for every 1°F increase in temperature, there is a 1.5 to 2 percent increase in electricity demand. As most power plants in Karachi depend on fossil fuels, this heightened energy demand contributes to increased air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, further contributing to the ongoing global warming cycle.

What can be done?

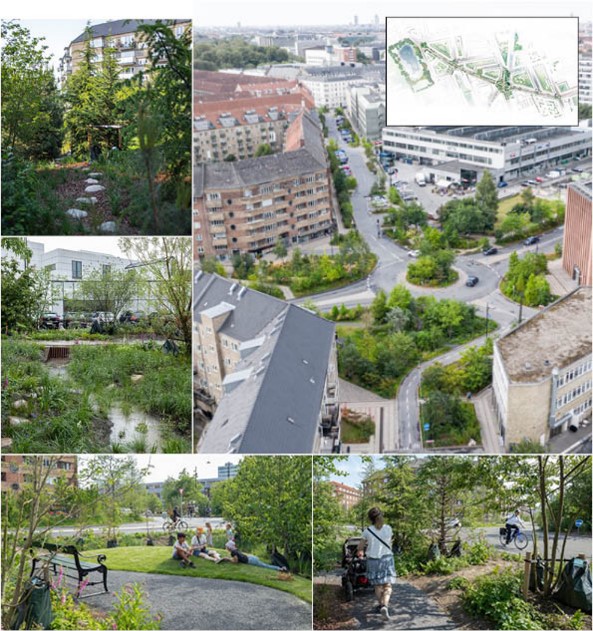

Scholars have been actively exploring effective ways to improve the urban thermal environment and decrease the negative impacts on cities. Urban parks stand out among the most reliable and natural remedies for extreme heat. Studies have shown that green spaces like urban parks and roadside greenways can significantly lower surface temperatures and overall city heat.

This is because they provide shade and evapotranspiration, creating a ‘Park oCol Island’ (PCI). Trees and plants in these areas block direct sunlight and release water vapor through evapotranspiration, cooling the nearby air and surfaces. This combination effectively reduces temperatures within parks and their surroundings, helping to counteract the urban heat island effect and regulate the nearby environment.

However, urban planners are still exploring the best places to plant trees and their effectiveness in Karachi’s specific climate. To address the growing problem of UHI, I would like to share insights from a recent research paper by Gajani (2024), highlighting the remarkable potential of Urban Green Spaces to cool down the city and revive its vanishing biodiversity.

This research identifies areas with the highest heat stress and locates thermal hotspots to prioritize the construction of green spaces in those areas.

The Cooling Potential of Urban Green Spaces.

To understand how much a green area can cool its surroundings, the study used remote sensing satellites to measure the land surface temperature (LST) across four different parks located in Karachi during the summer of 2022. LST is the temperature of the ground’s surface as measured from above.

The author then identified the “park cooling intensity,” which is the difference in temperature between the inside of the park and the area up to 500 meters outside the park boundary. The goal was to see how far the cooling effect of the park extends and how the temperature decreases as you get closer to the park.

Although temperature profiles fluctuate, all urban green spaces (UGS) in Karachi show a general trend of cooling. For example, the cooling effect in ‘Karachi Golf Club’ and ‘Clifton Urban Park’ extends to various distances, around 150 to 240 meters, and stabilizes beyond 420 meters for others.

This variation is often due to the size and shape of the parks, where it has been studied that larger parks tend to have a more pronounced cooling effect.

Researchers found unusual trends when studying the cooling potential of the city’s biggest park, Safari Park in Gulshan-e-Iqbal. Its cooling intensity values were recorded as negative. This might be due to the topography, where trees are mostly concentrated along the edges, while the central areas have limited tree coverage, leading to erratic fluctuations in recorded temperature.

This highlights the need for urban planners and administrators to prioritize preserving and enhancing the park’s design for effective urban temperature mitigation. When planning an urban park, its size and shape should be kept as a primary factor to consider.

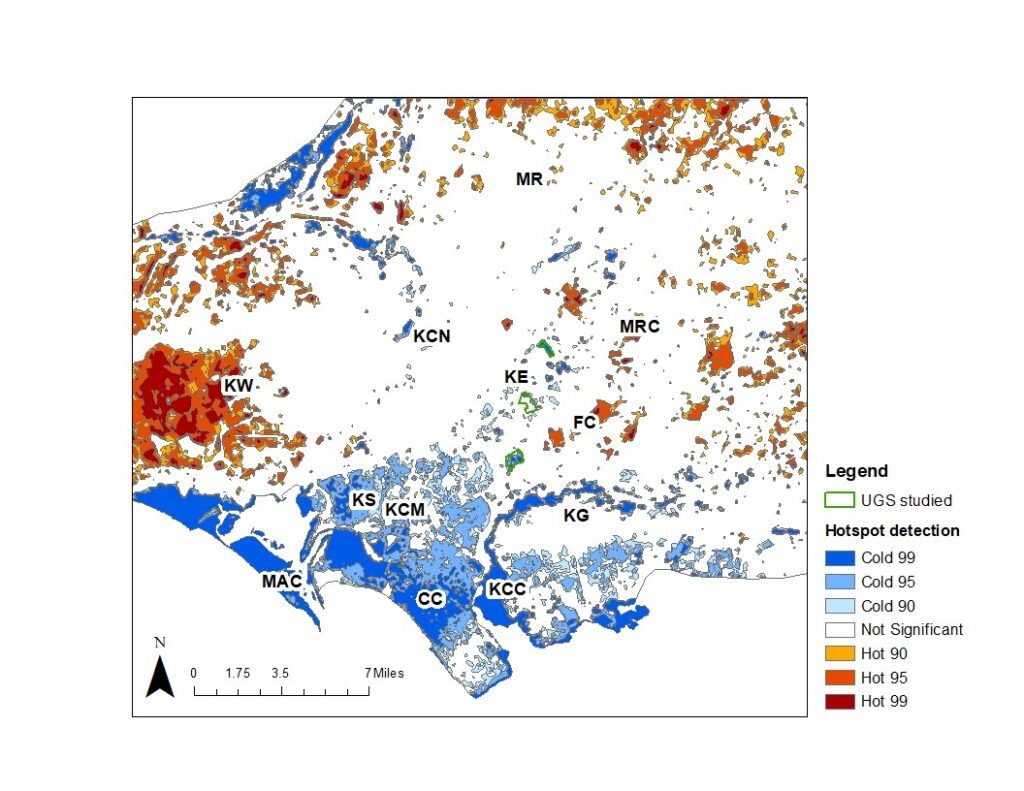

Thermal Hotspots— Detection and Analysis

To further analyze the thermal disparities within the city, researchers identified localized clusters of ‘Hotspots’ using the Getis Ord (Gi*) approach. These clusters represent areas where high LST values are grouped by other high LST values.

Results indicate that parts of Karachi face scorching heat due to large areas of empty land with little greenery. This is especially true in Karachi West district, where neighborhoods like Mauripur and Mangopir see average surface temperatures exceeding 42°C!

In contrast, areas with more parks and green spaces, like Karachi Central and East, have fewer hot zones and cooler temperatures.

Planting trees and creating green spaces in these vacant areas is key to making Karachi more comfortable. This would help reduce hot zones and cool down the entire city, benefiting everyone. The good news is that areas near the Arabian Sea, like Clifton and Kiamari Town, tend to be cooler.

This is because of cool sea breezes and the presence of the Karachi coastline’s mangrove belt. However, even these areas can get very hot during heatwaves. Buildings that are close together, poorly ventilated, and made with low-quality materials that can trap heat are making things worse.

This study highlights the power of urban parks as natural air conditioners, significantly cooling down their surroundings. By strategically planting trees in the hotspot areas, we can create a targeted plan to make Karachi a cooler, healthier city for everyone.

Educating both the public and city officials about the benefits of green spaces is key. Imagine a network of parks and tree-lined streets strategically developed in Karachi’s hottest districts, like Karachi West and Malir. This wouldn’t just bring down temperatures; it would create havens for recreation and improve our overall well-being.

Challenges in Developing Urban Green Spaces—Expert Insights and Solutions

According to a study conducted by the World Health Organization, it is recommended that each individual living in a sustainable city has access to a minimum of 9 m² of green space, with an ideal value of 50 m² per capita. Karachi falls significantly short of this standard, highlighting the urgent need for action.

I had the opportunity to talk with Mr. Rafiul Haq, a renowned environmentalist and expert in ecological management. During our conversation, we explored the social and technical challenges associated with developing a proper UGS system in the city.

Mr. Haq points out that one of the primary obstacles is finding appropriate space in the densely populated city where a long-term sustainable forest can thrive. The landscape layout conflicts with existing infrastructure, buildings, and transportation networks often act as physical barriers, making it difficult to carve out sizeable green zones.

Moreover, government agencies, NGOs, and even individuals only prioritize short-term visibility over long-term sustainability. Although there are frequent plantation drives across the city, these efforts often lack strategic planning.

Instead of merely planting trees for publicity, the focus should be on identifying and protecting areas where a long-term urban forest can be developed. This approach would ensure the survival and growth of green spaces rather than temporary improvements.

Additionally, he emphasizes the importance of selecting the right type of trees and the appropriate planting time to ensure their growth and sustainability. Many people are unaware of these factors, leading to ineffective plantation efforts. Karachi’s coastline also offers a unique opportunity to plant and protect mangroves, which are crucial for the ecosystem.

Therefore, sincere commitment and vision are necessary to ensure these green spaces are maintained and protected from urban encroachment and poaching.

He suggests creating ‘peri-urban forests’ in Karachi when asked about the way forward. These forests would be located on the outskirts of the city, where there is currently mostly barren land. These peri-urban forests would act as green buffers around the city, significantly reducing the urban heat island effect and improving air quality.

He emphasizes that this transformation requires not only planting trees but also selecting species suited to the local climate and conditions and that proper patience is crucial as these forests need time to mature and become effective.

As we face the escalating challenges of urban heat and climate change, it becomes clear that the responsibility to create a sustainable future lies with each one of us. Transforming Karachi through the establishment of urban green spaces is not only an environmental necessity but also a moral obligation. Robert Swan wisely pointed out,

“The greatest threat to our planet is the belief that someone else will save it.”

It is time for every citizen, planner, and policymaker to step forward, act, and commit to greening our city. Doing so can alleviate heat stress, enhance air quality, and forge a habitable environment for future generations. Let’s embrace the challenge, for a greener Karachi is a healthier, happier Karachi for all.

References:

- Gajani, A. M. (2024). Spatial patterns of urban heat islands and green space cooling effects in the urban microclimate of Karachi. In arXiv. https://doi.org/10.31223/X5VQ4X

- NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, Monthly Global Climate Report for April 2024, published online May 2024, retrieved on May 19, 2024 from https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/monthly-report/global/202404.

- Eckstein, D., Winges, M., Künzel, V., Schäfer, L., & Germanwatch Körperschaft. Global Climate Risk Index 2020 Who Suffers Most from Extreme Weather Events? Wether-Related Loss Events in 2018 and 1999 to 2018.

- Russo A, Cirella GT. Modern Compact Cities: How Much Greenery Do We Need? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018 Oct 5;15(10):2180. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15102180. PMID: 30301177; PMCID: PMC6209905.

- Pakistan launches major study on the impact of heat on pregnant women and babies | Dialogue Earth. (n.d.). Retrieved May 17, 2024, from https://dialogue.earth/en/climate/pakistan-investigates-effect-of-heat-on-pregnant-women-babies-through-major-study/

- Mentaschi, L., Duveiller, G., Zulian, G., Corbane, C., Pesaresi, M., Maes, J., Stocchino, A., & Feyen, L. (2022). Global long-term mapping of surface temperature shows intensified intra-city urban heat island extremes. Global Environmental Change, 72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102441

- UN-Habitat Pakistan Country Report 2023

More from the author: Sustainability in Astronomy — A conversation with Dr Leonard Burtscher from “Astronomers for Planet Earth”

Aly Muhammad Gajani holds a Master’s degree in Space Science and Technology, specializing in Astrophysics together with GIS applications. His research focuses on galaxy evolution, astrophysical cosmology, exoplanet detection, and computational astronomy.