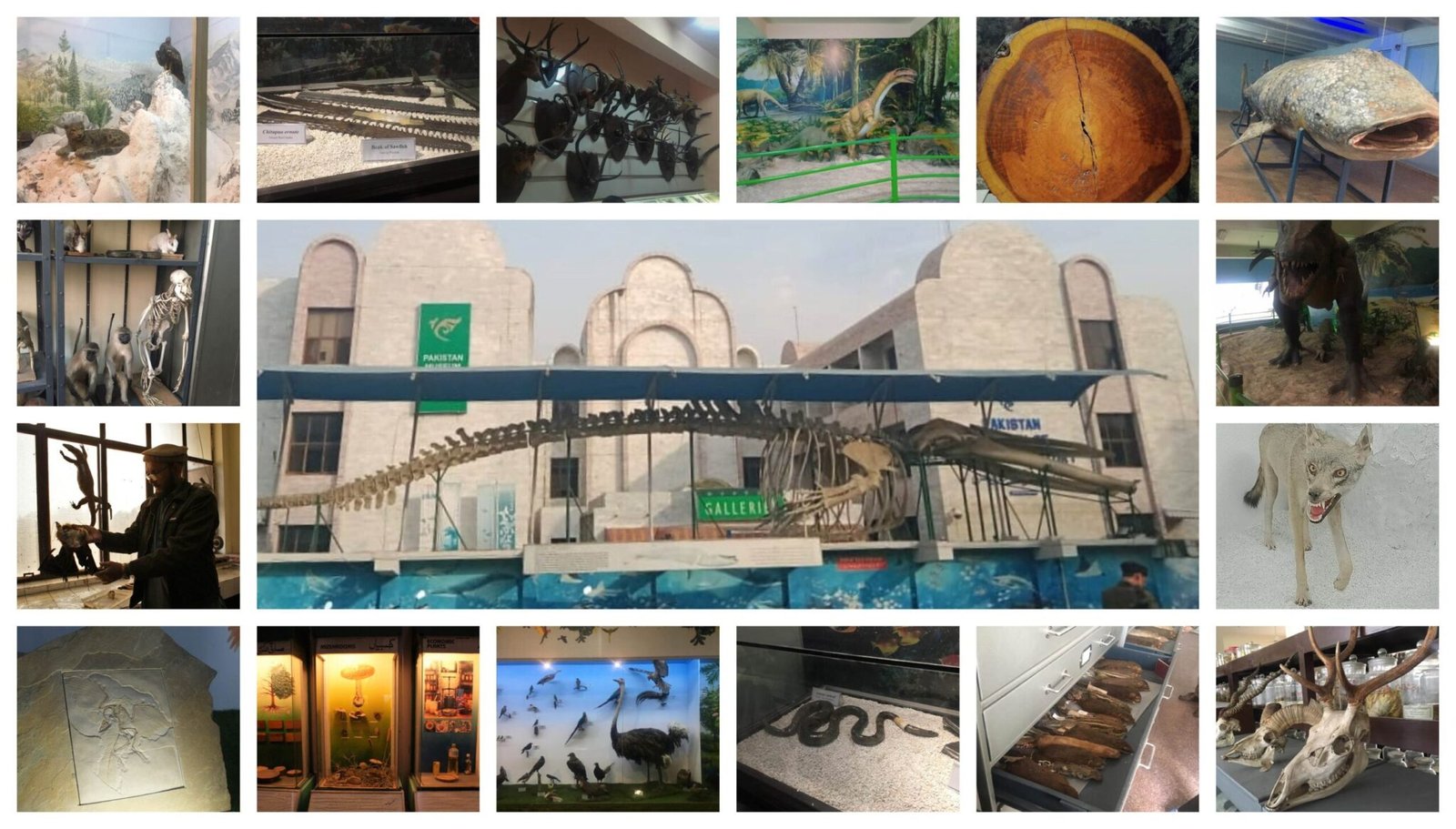

Corresponding to the theme of our wildlife edition, we decided to take a tour of the Pakistan Museum of Natural History (PMNH) that is located near Shakarparian National Park, Islamabad. Housing more than 1.4 million specimens, the museum features extensive collections of wildlife and nature reserves. Other than sections for the public, it also has labs for Taxidermy of animals and allows researchers to work on their projects. It is currently managed by Pakistan Science Foundation under the Ministry of Science and Technology.

Our team was lucky enough to visit the museum and have an exclusive look at their collections for researchers. Mr. Muhammad Asif, who is an Associate Curator at the Zoological Sciences section, graciously gave us the tour of the entire museum. Following is our conversation and interview with him about PMNH.

Team Scientia: We are thankful for giving your time, Sir. Shall we start the tour?

Mr. Asif (Tour Guide): Sure. So, most of the things here in the museum are related to mammals, specifically their taxonomy. There is a researcher here for every discipline and tasked with looking into the matters related to their field.

Here, we have our research block, which includes our reference collection from all over Pakistan. Ph.D. students from different universities come here and work on collections as per the requirement of their advanced research. From Molecular Biology to Genetics to Classical Taxonomy and other research fields, everything is included.

This is our Entomology lab. We had a project where the goal was to collect and preserve all the butterfly species in Pakistan. Other than butterflies, various other groups of insects have also been displayed here.

TS: Are these crafted models? What are they made up of?

TG: No. These are bodies that have been preserved via the process of stretching. It begins with the collection of animals in the field, especially insects.

TS: Are all these displayed species from this region (referring to Pakistan)?

TG: Yes. PMNH tends to collect the COMPLETE collection of rocks, minerals, flora, and fauna of a particular region for ease of reference and research. This gives us the complete picture of a region and what kind of wildlife, animals, etc. it inhabits, under one roof.

TS: And does the general public have access to these collections? What if some member of the public wants to observe and work?

TG: This section is specifically for researchers. The displays on the first floor are for the general public.

TS: Coming back to the preservation process of these insects, can you please elaborate on the process of stretching?

TG: So, we begin by simply preserving them in the core and bringing here in the labs. After that, Pinning is done i.e.; we give them different positions on a thick board with the help of pins. In the case of insects, they have an exoskeleton made of Chitin, which is very hard. Their legs also need to be adjusted to set them in a proper posture. Pins are used to fixing them at the place.

TS: What about the new species that are being discovered or are not a part of these assortments? After how long do you review your collections?

TG: We keep sending expeditions to the wild from time to time. It depends on the focus group of the research team. Students work on their species of interest, but our goal is to ensure the availability of all the species present in Pakistan here at our respective sections. Other than that, people donate foreign or exotic species as well, which we add to our displays and collections.

We have almost all the specimens of the bird species in Pakistan. Many of these are migratory as well, especially the ducks.

TS: Wow, there are so many! These preserved animals look so fresh! For how long do they remain unwithered?

TG: The process is known as Taxidermy. When a bird or animal dies, skinning is done. It is easier and shorter for birds as their skin is not as thick. Mammals and reptiles require more time.

After skinning, dehydration is performed, and then chemical preservatives are applied. It is followed by stuffing. For that, casts are made, the posture is prepared, the skin is mounted, and the final touches are given. The specimens are preserved and good to go for almost 20 years, but if bacteria invade, this time may decrease, and we will have to refresh it.

We also have the depository of freshwater fishes and amphibians. This section covers all the freshwater fishes and species of Pakistan though the amphibian collection is not complete due to the lack of input to it.

TS: Are there other special methods for the collection?

TG: Yes. There is wet and dry preservation. Stuffing comes under dry preservation. Preservation done in chemicals is wet. There are further two types in wet: via alcohol and formalin. We are gradually shifting to alcohol because formalin is carcinogenic, and the coloration of the specimen also changes when it is used.

TS: Being students of Biochemistry, we have studied that snake venom is used for designing pharmaceuticals and vaccines, etc. Given that you have an extensive collection of snakes, do you provide companies samples if they need it?

TG: No, because we preserve in wet. The venom is stored in a pouch above the head. And it denatures with time. For that purpose, NIH has the venoms that can be used in drug development, so most companies contact them.

TS: So, how do you decide where and in which section to put an animal? Do you classify geographically?

TG: We create it taxonomically, not geographically. By orders, species, etc. or based on morphological features. It is the job of the taxonomist to classify and decide using the features of the specimen. Mr. Riaz here does Taxidermy.

TS: AOA, Sir! Please do share the process with us.

Mr. Riaz: So, the steps are as follows: The specimen is cut at the center, and a wire is inserted into the legs and wings followed by mold. For example, this here is a bat. The muscles are made to denature. If traces are left, then long-term storage of the specimen is not possible.

So, we take it out completely and fill it with cotton, plaster of Paris, and poly compounds, mainly polyurethane. These are used to preserve body shape as they are light-weight and easy to maintain.

TS: Are they renewed from time to time?

Mr. Riaz: Yes, definitely! And that is due to the ectoparasites present on the skin. For that, specimens to be processed are placed in a freezer. The temperature is -30 degrees, and it kills the ectoparasites. The specimen is then taken out, and further processing is proceeded with.

TS: That’s great. (Moving on to the next section)

TG: This right here is our Pre-Partition Collection. It includes vertebrates and marine wildlife, among others. Before partition, there was the combined Zoological Survey department for both regions. After partition, Pakistan’s collection was set up in Karachi. But there were some issues related to the museum’s building, so the collection was shifted here. We have mammals, birds, and reptiles, etc. preserved here as well. Our collectors go to deep and far regions around the country to get these animals. For instance, we have sent deep-sea expeditions from Balochistan to various other ranges.

We also have here our bird collection. We have placed the same species within these drawers. For hair and DNA analysis, our specimens come into use.

TS: That’s quite impressive. On your website, there was a mention of a biodiversity database. Can you share what that is?

TG: That is the complete database of all our collections. We have a link with international GBIF as well. We are working on that.

We also have exotic species like ostrich etc. Zoos of different cities have contact with us. When an animal dies, they donate the specimen to us.

TS: Speaking of exotic species, there was a lot of uproar recently on social media when a license was given for hunting of Houbara Bustard. Is hunting of endangered animals in Pakistan being done to a large extent?

TG: That is really not the case. Several initiatives are being taken to conserve animals like Houbara Bustard and Markhor. Their population is relatively stable, and to prevent any more damage, trophy hunting is allowed once in a while. But it should be noted that even if there are special rules and regulations, the local hunters do more damage than the foreign. And as far as these birds are concerned, they come from different migratory routes and are also hunted along the way in regions of Central Asia, Russia, etc. So, it’s not just that they are only hunted in Pakistan.

TS: What about Markhor, the national animal of Pakistan? Is it still considered endangered?

TG: Actually, endangered species are those whose quantity in their natural habitat is less than 2000. Such are classified into the “Endangered” category. Markhor is not endangered as it is well above the limit in the wild. And it varies with each animal. For instance, Black Buck is extinct in the wild. But its breeding in captivity is being done at the Lal Suhanra National Park in Bahawalpur. Its active habitat is not available anymore, but it is present in quite a large amount in captivity. But there are many other species under threat in Pakistan e.g.; the snow leopard has been recently added to the list of endangered species as well as the leopard in the Margalla hills.

TS: We see. What about the public section?

TG: This public section features various displays. There is a depiction of prehistoric life in caves. We also have displays of wildlife in the coastal area, specifically Hawkesbay. The turtle preserved with its eggs link to that. Other animals include crocodiles, pangolins, and otters, as you can see for yourself. These animals are under threat as well. Otter is now considered endangered here due to fish farming, and pangolins are being trafficked at a very high rate.

We keep introducing changes in the museum every now and then to appeal to the public. For example, this is the Ecology section that we developed a while back. It shows the food chain concept in a simple and basic manner for the understanding of young children. All these other displays are curated specially for the younger audience.

TS: What about this giant tree trunk?

TG: This is a transverse section of a tree trunk dating back to many years. It has its annual rings that can tell about its age. It can also tell us about the weather. We can tell that by looking at the circles within its trunk. When there’s rain, growth increases, and so does the distance between the rings. During harsh conditions, there is petite growth, so the rings are dark and narrow. We can predict the weather history the tree grew in.

TS: So, how much biodiversity is there in Pakistan? Compared to other regions?

TG: The more biomes there are, means the more species there are. Pakistan has quite a large number of diverse species, almost all of those in South Asia. At our biodiversity section, we cover all zones from the coastal areas to the peaks of mountains.

TS: Climate change is a very hot topic these days. We also see its effects around the world, from Australian wildfires to flooding across various regions. Is wildlife at threat from climate change in Pakistan as well?

TG: Not really. We have changes in this region as well, but mostly we have the normal phenomenon of earthquakes, heavy rainfalls, and snowfalls. And as these are all-natural processes, there is flexibility in the environment to absorb its effects, and they can help in biome regeneration as well. But for species that became extinct in Pakistan, the major threat was and still is, urbanization. When their habitats are destroyed, the ultimate effect is on its population and survival. As you can see in Australia, there is a natural calamity happening at the moment, and within the next five to ten years, the surviving species will be able to regain their survival rate hopefully.

TS: Please tell us about the Baluchitherium? (Referring to the life-size model standing in the PMNH grounds)

TG: It is the largest mammal ever found in this area. It was found in Dera Bugti, which has lots of vegetation. The Baluchitherium was a herbivore and required tons of thick vegetation to feed daily. Scientists from Switzerland signed a joint project with PMNH to find out more about it and its lifestyle.

TS: It looks quite a lot like the dinosaur. Is it its ancestor?

TG; No, not at all! The dinosaur was a reptile, and this was a mammal. They are not linked.

TS: All of your collection is so great. Why is there such a huge gap with the public? We looked at socials of other foreign organizations like American NMH on social media and other platforms. They have so many ongoing events that actively engage the public. On the other hand, your social page is quite dormant. Why is that so?

TG: Yes, we acknowledge that we do face problems. This right here is not a government priority. We do not get satisfactory support and funds. As you can see for yourself, the building construction has been incomplete for thirty years. We are trying our best we can with the resources we have. We often have events for the public, and students from schools also visit the museum fairly regularly.

TS: So, you not given enough resources and funds for the museum?

TG: Yes, there is not enough funding from the government. We have other different resources. We also collaborate with various international organizations, and funding is provided for research projects. We have an ongoing collocation with China, and we frequently work with other European countries on different programs.

TS: How is the public response?

TG: The Public response is quite good; visits increase day by day. According to our current data, we had almost 165,000 visitors in the last six months till December. The number of total visitors in the year is expected to add up to 195,000. Most of our public activities are concerned with students from schools and colleges.

TS: That is good to hear. We are so grateful for your time and this tour! Thank you so much.

TG: My pleasure!

Needless to say, we were much amused by the displays in the museum. So, the next time you are in Islamabad, make sure to check it out and see the great collection for yourself.

Also Read: A Candid conversation with Mother-Daughter duo on Nature & Wildlife photography

Image Credits: Scientia Pakistan