For centuries, women have made important contributions to the sciences, but in many cases, it took far too long for their discoveries to be recognized — if they were acknowledged at all. And too often, books and academic courses that explore the history of science neglect the remarkable, groundbreaking women who changed the world. In fact, it’s a rare person, child or adult, who can name more than two or three female scientists from history — and, even in those instances, the same few names are usually mentioned time and again.

Now it is time to change that! In this blog post, we’re sharing the stories of some historic female scientists who blazed new trails in their disciplines. From determining the size of the universe to unlocking the secrets of the genetic code, these women have forever changed the way we see our world. And if you’d like to learn more about any of the featured women or introduce them to children and teens, after each profile we’ve shared several reading recommendations for different age groups, as well as other resources that celebrate these women of discovery.

Maria Merian (1647 – 1717)

Before German-born naturalist and scientific illustrator, Maria Merian began to study the life cycle of butterflies, most people believed that they were “born of mud,” spontaneously generated out of the earth. Her interest in insects was unusual; they were considered “vile and disgusting” and hardly worth study. She was also one of the first naturalists to observe insects directly, giving her remarkable insights into the way they really lived. Although she emerged as one of the leading entomologists of her day, since she wrote in German and not in Latin, the official language of science at the time, her remarkable discoveries about the metamorphosis of insects were ignored by many scientists. She also raised eyebrows by funding her own, unofficial expedition to Suriname where she described many new insects and plants; a highly unusual venture for a woman of the period to undertake. Even so, her impact on science is undeniable: many of her classifications are still valid today and her exquisite paintings of plants, animals, and insects have been widely admired throughout the centuries.

Marie Skłodowska Curie (1867 – 1934)

As the first woman in history to win a Nobel Prize — and the only person to win two Nobel Prizes in two different disciplines (chemistry and physics) — Polish-French physicist and chemist Maria Skłodowska Curie is one of the first names that comes to mind when thinking of women in science. When she and her husband Pierre Curie discovered radioactivity, it changed the way people saw the world forever: suddenly, it appeared that energy could appear as if by magic. She also discovered two elements, polonium and radium, and the element curium is named in her honor. The world’s first studies into the treatment of tumors took place under her direction and she founded the Curie Institutes in Paris and Warsaw, which to this day are leading medical research centers. Beyond her incredible individual contributions, Marie Curie has also left another enduring legacy — she has inspired generations of women to pursue their own dreams of scientific exploration and discovery.

Henrietta Leavitt (1868 – 1921)

Today, a computer is a machine, but in Henrietta Leavitt’s day, the term referred to a group of female astronomers who had been hired by Harvard to analyze data from their observatory. Edward Charles Pickering, who hired Leavitt, assigned her to look at variable stars: these stars brightened and dimmed at predictable intervals. Using the data provided to her, Leavitt identified and classified over 2,400 of these stars — and discovered that there was a relationship between the period and the luminosity of a particular type of variable stars, the Cepheids. This discovery changed the way astronomers saw the universe: not only did it allow scientists to measure the distance to remote galaxies, but it also paved the way for a new understanding of the structure and scale of the universe.

Helen Taussig (1898 – 1986)

Helen Taussig’s journey to a career as a physician wasn’t easy: she struggled with severe dyslexia, hearing loss from a childhood illness, and discrimination due to gender before she received her medical degree from Johns Hopkins in 1927. After overcoming these challenges, the American physician went on to found the field of pediatric cardiology. She is best known for discovering the cause of “blue baby syndrome,” a birth defect of the heart that had a very high mortality rate. After Taussig developed the concept for a repair procedure, she worked with two of her colleagues at the Johns Hopkins Hospital to design a technique that has saved the lives of thousands of babies. She continued her research work until the day of her death at the age of 87.

Barbara McClintock (1902 – 1992)

When the American geneticist Barbara McClintock took her first course in genetics at Cornell’s School of Agriculture in 1921, she was immediately fascinated and knew that she would remain “with genetics thereafter.” In 1948, she discovered that segments of genetic code in maize could change positions on their chromosomes — but since scientists didn’t believe that genes could change except by mutation, other researchers responded to her work with “puzzlement, even hostility.” While she continued researching controlling elements throughout her career, she stopped publishing papers about them in 1953. It wasn’t until the late 1960s that geneticists realized the significance of genetic transposition and the trailblazing nature of McClintock’s research. McClintock became the only woman to win an unshared Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1983. She once said, however, that her greatest satisfaction in life was discovering a secret that no one else had known: “If you know you are on the right track, if you have this inner knowledge, then nobody can turn you off,” she once said. “No matter what they say.”

Jane Goodall (b. 1934)

At a time when female scientists were often considered too fragile and emotional for fieldwork, Jane Goodall proved everyone wrong. The British primatologist is considered the world’s foremost expert on chimpanzees after her 55-year-long study on the wild chimpanzees in Gomber Stream National Park in Tanzania. Goodall was the first person to observe tool creation and use — something previously thought to be exclusive to humans — in chimpanzees when they fished for termites with specially prepared sticks. Goodall is also a dedicated advocate and activist on behalf of animal welfare and conservation causes. Equally importantly, she has inspired generations as an example of women in science. Her dream of traveling to Africa as a child was laughable at the time “because we didn’t have any money, because Africa was the ‘dark continent’, and because I was a girl”; now, everyone knows about the watchful young woman who changed the definition of humanity.

Rita Levi-Montalcini (1909 – 2012)

Before Rita Levi-Montalcini could even complete her education, the Jewish Italian woman was already facing limitations on her career from fascism and anti-Semitic laws. And yet when World War II broke out, she chose to stay in Italy and created a makeshift laboratory in her home so she could continue her work. After the war, she moved to the US, where she and a colleague discovered nerve growth factor, a protein that regulates the growth of cells and plays a particularly important role in the development of tumors. However, it took almost 30 years before the discovery was fully recognized by the scientific community and she was granted the Nobel Prize in Medicine. By the time she died, Levi-Montalcini was the oldest living Nobel laureate — and the first Nobel Prize winner to live to 100.

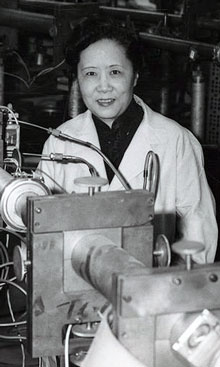

Chien-Shiung Wu (1912 – 1997)

Chien-Shiung Wu was born in China, but at the recommendation of one of her supervisors, she set off for the US in 1936 to attend the University of Michigan for her Ph.D in nuclear physics. However, when she learned that women weren’t allowed to use the front entrance at Michigan, she changed her plans and attended University of California, Berkeley instead. As a part of the Manhattan Project during WWII, she helped develop the process for separating uranium metal into various isotopes. She is best known for conducting the Wu Experiment, which disproved a hypothetical physical law called the conservation of parity; her experiment paved the way for several of her colleagues to win the 1957 Nobel Prize in physics, although the Nobel Committee overlooked her contributions. In her later career, she also became outspoken about sexism in the sciences: “I wonder”, she asked at a 1964 symposium, “whether the tiny atoms and nuclei, or the mathematical symbols, or the DNA molecules have any preference for either masculine or feminine treatment.”

The Blog originally posted on, A mighty Girl and posted here with prior permission.

Also Read, Katherine Johnson dies, a woman who broke barriers at NASA.