As this year’s summer rolls in, it brings with itself fears of hot and humid hours of no escape from the angry sun and no air conditioning as power is cut intermittently across the country, sometimes for several consecutive hours. Suppose you’ve ever sat through one of those episodes where the electric supply from the company is cut off at midday with no backup available. In that case, you likely are well aware of the ensuing mania that engulfs the subject of this treatment.

And anybody made familiar with this situation begins to understand the fundamental flaws in our modern architecture, which cause the buildings to be very energy-inefficient and subject to fluctuating temperatures. You find yourself horrified at the sheer potency of the hot weather and begin to sympathise with the people with no access to electricity.

You may even have included your ancient forefathers in the list of people who had it tough regarding the weather. Here is where you might not know something about the ancient people of Indo-Pakistan. They were actually very well accommodated within their locales, no matter the climate.

It is a surprise to many of us that hundreds and thousands of years ago, people living in the exact geographical locations as ours were living just as, if not more comfortably, under the same weather. Whereas our modern houses and buildings start to feel like a pan over the stove as soon as the calendar hits May, ancient buildings retain constant cool temperatures throughout the season.

And all this with no air conditioning or electricity consumption. The ancients had slowly learned and built up their art of indigenous architecture over several centuries, allowing them to build the perfect passively-cooled homes without ever needing electricity.

In fact, their techniques were so excellently adapted to their locations that scientists have been looking to implement their techniques in urban construction to reduce energy wastage and greenhouse gas emissions. According to International Energy Agency, it is reported worldwide that buildings consume almost 34% of the energy produced annually (almost 153 quintillion joules)1. In light of this incredible statistic, here are a few ways in which modern architecture could benefit from the distilled wisdom of the ancients.

Building Materials

It would not be an overstatement to say that building materials are perhaps the most crucial factor in determining the eventual “thermal comfortability” of a building. The material used in roofs, ceilings, walls, and floors should show up in budget tracking and be considered for its eventual insulating and cooling abilities.

Modern buildings extensively use cement and steel for the bulk of the structure. While widely available and structurally durable, they are a recipe for a thermally-inefficient outcome. Studies have shown that these materials are not only practically ineffective2 at keeping out heat when compared to traditional materials but also contribute a weighty 13.5% of global CO2 emissions annually (almost 4.9 billion tons)3.

Compared to this, traditional materials sourced locally – thus saving the need for extensive transportation and processing – not only have a smaller carbon footprint but have also been proven to have specific cooling properties. For instance, a study published in 2019 found that using limestone in buildings reduced summer heat gain and winter heat loss due to its innate physical properties4. Similarly, using wood, straw, clay, and other naturally occurring materials also helps decrease the cost and temperature.

The ancients had slowly learnt and built up their art of indigenous architecture over several centuries, allowing them to build the perfect passively-cooled homes without ever needing electricity.

Ventilation

It is common knowledge that a well-ventilated room will fare much better than a closed-off space when it comes to fighting off the radiating heat. However, natural ventilation as an alternative to electrically powered air-conditioning is a rarely sought option, mainly because of the lack of expertise in utilising the natural flow of air. Despite the availability of the knowledge of convection -that hot air rises to the top, while cold air sinks to the bottom -very few modern buildings use this dynamic to reduce the cost of air-conditioning and its associated impact on the impact.

While the ancients were arguably unaware of the precise reasons for the convection phenomenon, they calculated their architecture around it. This would include the placement and size of the windows, the installation of wind-catchers in ceilings, and the placement of smaller openings along the lower half of the walls. In Shahjahanabad, India, windows of small diameter are placed strategically on the walls at ceiling and floor level. This allows for the cold draft to enter the room from the ground-based windows and the hot air to exit from the top5.

Similarly, 300 years ago, the people of Delhi were placing paper or straw screens soaked in water in the doors and windows of their homes. This caused any and all air passing through the screens to cool down by evaporation6.

Vegetation

While vegetation and leafage certainly serve to bring about a sense of peace and beauty to any architecture, it should be noted that aesthetic value is not the only benefit it renders. According to a 2014 study, vegetation cover on the ground, including grass, shrubs and other herbage, tends to reduce the potential summer temperatures, while a “green roof” – which is the presence of foliage cover provided by plants to the roof – serves to reduce the cooling load of the building by a considerable percentage7.

The ancients extensively used vegetation and greenery in their buildings and surroundings, even if not by choice. Their towns and cities boasted a much greater green cover than our cities do today. The shade provided by the trees helped block direct sunlight, which kept the indoor temperatures low. Combined with the transpiration and evapotranspiration that resulted from the verdure, the resulting temperatures were shockingly cool.

Even today, closely packed urban areas are, on average, 1-3°C warmer during the day and almost 12°C warmer during the evening8 than a rural settlement which is broken up by vegetation allowing for ventilation and providing shade. This phenomenon has been dubbed the “Heat Island Effect” by researchers.

Insulation

A prevalent passive method of reducing or even curbing heat exchange across a boundary is adding layers of non-conducting material. The best non-conductor of heat is air. We can minimise heat exchange by using porous materials that can hold air in large quantities in a small space. Using polystyrene, fibreglass, cellulose, and mineral wool as the insulating materials can reduce heat gain to the house interior.

Although the ancients did not have access to any of these modern insulating materials, they used natural fibre in their buildings, such as dried grass in thatched roofs and straw in the adhesive and plaster for their walls. Both grass and straw create natural insulation due to their hollow structure, bringing about lower temperature fluctuation in the interior of the house throughout the day.

Today, the herdsmen of the Mongolian steppe use wool as a tarp for their yurts and wool carpets to prevent heat loss from the ground. It works perfectly for them during the harsh winter, and with some science, it can work for us during the hot South-Asian summer.

In addition to that, ancient fortified buildings also made use of thicker walls, which delay heat exchange and provide more relaxed interiors. There was also the practice of leaving the space between two layers of walls hollow. Such an architectural feature can be found in the buildings of the Mughal era, such as the Badshahi Mosque of Lahore, Pakistan.

In some “heat capitals” of the world, notably in the Northern and Western Subcontinent, the custom of having subterranean chambers was prevalent. This used the surrounding soil to act as insulation and provided a cooler escape during the hot days of summer9.

Exterior Additions

Arguably exterior additions do not contribute as much to the total energy saving of the building; however, their effect cannot be refuted entirely. As seen in a 2017 study, the mere presence of a body of water near or around the building reduces the atmospheric temperature. This could be in the form of a lake, a moat, or even a courtyard fountain10. The ancients who settled on the shores of seas and the banks of great rivers enjoyed the perks of the evaporative cooling caused by the water.

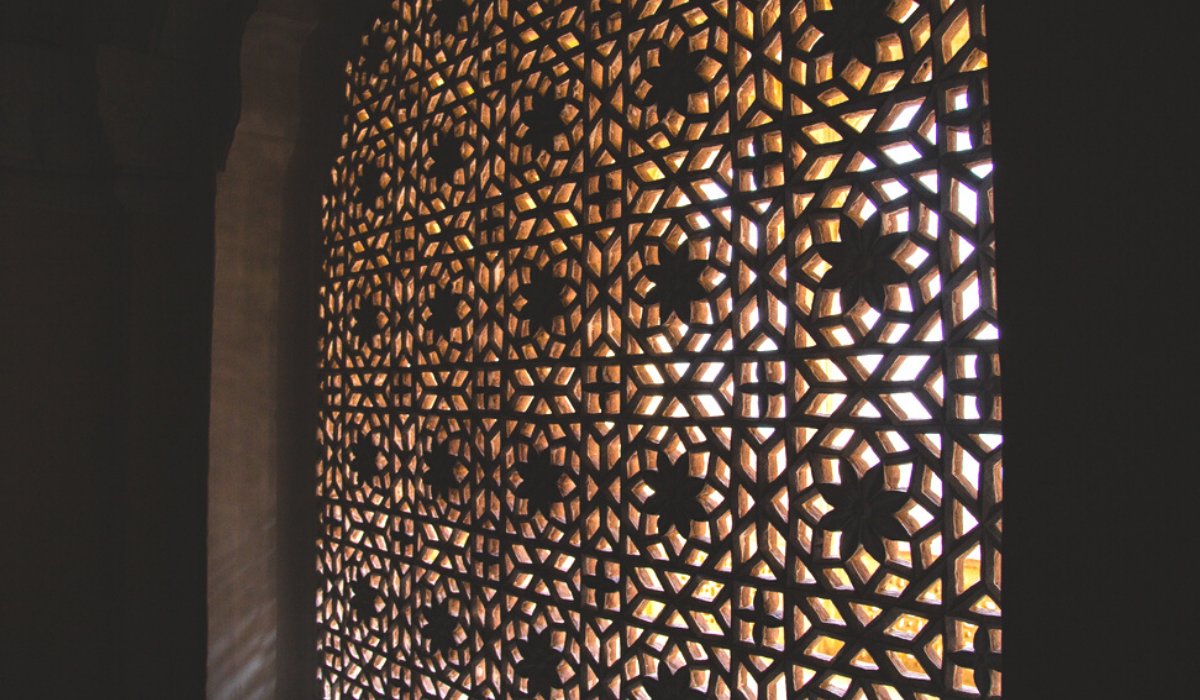

Moreover, the presence of stone or wood latticework around many medieval builds helped reduce the surface area of direct sunlight while allowing ventilation. Such “Jaalis” are ubiquitous in Indo-Islamic architecture. Their modern form is called a Brise-soleil, which is now a part of many modern buildings.

Finale

The lifestyle of the generations before us is not very attractive to most of us, and while it is a good idea, in general, to move forward and live in the present with our own unique identity, it is crucial not to deny any and all credit to the people of the past. Indeed, some of their architecture has stood the test of time, and despite nature’s continuous wear and tear, their monuments stand tall.

There is shrewdness in studying the knowledge of the past and applying it as a modern concept, for despite the inconceivable technology gap between them and us, there will always be something we can learn from them.

References:

- 1 https://www.iea.org/reports/buildings

- 2 Pandit, R. K., Gaur, M. K., Kushwah, A., & Singh, P. (2019). Comparing the thermal performance of ancient buildings and modern-style housing constructed from local and modern construction materials.

- 3 https://www.imperial.ac.uk/news/235134/greening-cement-steel-ways-these-industries/

- 4 Sharma, A. K. (2019). Evaluation of different building designs to enhance thermal comfort or comparative study of thermal comfort in traditional and modern buildings.

- 5 Gupta, N. & Centre for Energy Studies, Indian Institute of Technology Delhi. (2017). Exploring passive cooling potentials in Indian vernacular architecture

- 6 Dalrymple, William. (2006). “The Last Mughal: The Fall of a Dynasty, Delhi 1857”

- 7 Perini, K., Magliocco, A., Effects of vegetation, urban density, building height, and atmospheric conditions on local temperatures and thermal comfort. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening (2014)

- 8 https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/city-hotter-countryside-urban-heat-island-science-180951985/

- 9 Dalrymple, William. (2006). “The Last Mughal: The Fall of a Dynasty, Delhi 1857”10 Subramanian, C. V., Ramachandran, N., & Senthamil Kumar, S. (2017). A Review of Passive Cooling Architectural Design Interventions for Thermal Comfort in Residential Buildings

Also, read: Climate Change and Residential Buildings – The way forward

Haseeb Irshad is a neophyte connoisseur of academic writing, whose interests range from medicine, bio-molecularity, and environmental and ecological studies to pop-culture TV and films. He also indulges in fiction and religious studies from time to time.