Cameras flash. The courtroom is more of a film set than a court of justice for a crime turned spectacle. Millions of people observe it through their phones and break down every look, every inhalation, and every tear. TikTok is swarmed with videos marked as evidence. YouTube gurus pass their judgment each day, way before the jury. It is streamed, clipped, and hashtagged.

From the trial of Johnny Depp-Amber Heard to Making a Murderer, courtroom drama has become entertainment all over the world, and somewhere in between crime, clicks, and courtrooms, truth begins to lose definition.

Everyone’s a detective now.

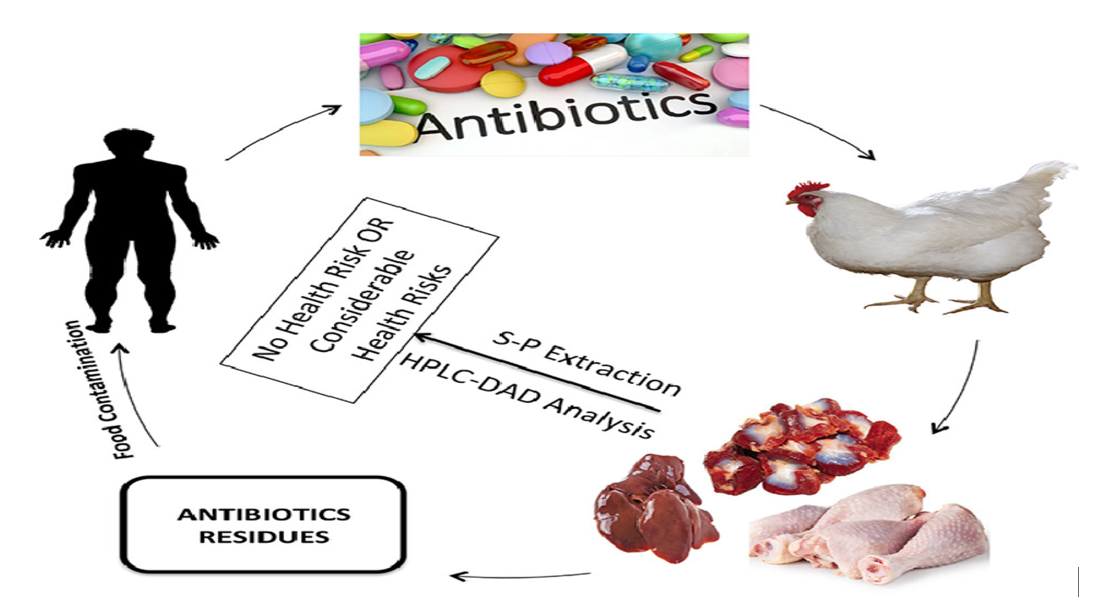

The last 2-3 decades of television and social media have made forensics an entertainment; it has taught us that any crime has a perfect trace, and that the truth will always be covered in lab lights and DNA results.

Real life isn’t that neat.

The Birth of the CSI Effect

CSI was not just a hit but was a cultural phenomenon when it was first aired in the early 2000s. Laboratory work was glamorized through the show. Murderers were resolved with investigators in designer clothes in 45 minutes. Blood patterns glowed. Computers solved them within a few seconds.

In reality, forensic scientists could not have an opportunity to look away. Courtrooms began to change, where jurors mostly demand solid evidence, including DNA, fingerprints, digital trail, etc. They had faith in evidence they had watched on screens, not in testimony they had heard.

Scientists began to refer to it as the CSI Effect, caused by media, especially shows like “Crime Science Investigation”, and is seen as a misleading expectation that shapes what jurors and the public expect in real trials. This phenomenon is typified by the hope that forensic evidence is always available, flawless, and rapid. This is likely to cause jurors to ignore non-science-based evidence or a feeling that a crime cannot be solved without a gun or forensic evidence.

Was it real?

The meta-analysis subsequently establishes that watching crime dramas had a minimal effect on the verdicts. Nevertheless, the expectations of jurors were certainly influenced by TV, and they believed that all evidence in a trial had to be forensic.

The irony? The CSI Effect does not need to be massive to be significant. How justice is practiced can be altered through even a slight change in people’s expectations.

When Fiction Becomes Public Truth

Real-life crime programs were the next to burst.

Making a Murderer…… Mindhunter….. The Staircase….

Every episode was full of truth and closure. However, the editing of the story was done as a thriller behind the camera. Heroes, villains, dramatic revelations, and justice were packaged for viewers. Individuals began to think that they were knowledgeable in forensic science. Bloodstains told stories, fiber evidence had the power to convict, and DNA solved everything.

But it didn’t…

Real forensic work is slow, messy, and often uncertain. Samples degrade, labs backlog, machines fail… However, everything was clear and definite in the media version, and that’s where the danger lies. The difference between the reel and the real, and when such a distance goes to court, it may distort justice itself.

The Digital Crime Scene

Not every crime results in bodies and blood. Some live inside screens. A deleted text, a hidden server, a photo in the cloud….

It is at this point that digital forensics comes in, the art of tracing the digital fingerprints. It does not concern magnifying glasses and powders. It’s about code, data, and logic. Professionals check phones, computers, and networks to reclaim the lost or deleted data. Each click, each message, each log, may tell a story.

Nevertheless, digital forensics is not television; it does not have a magic data recovery button. It is meticulous research, finding, gathering, and providing evidence in a manner that can withstand in court, and the stakes are growing.

Online fraud, ransomware and cyberattacks are literally everywhere. Digital forensics has become an essential component of justice, yet it encounters massive challenges, legal loopholes, a lack of tools, and the endless development of malware. Nevertheless, it is the new frontier of the truth that lives in the unseen corners of the internet.

When Your Fridge Testifies

Today, smart devices are what the world operates with. Your automobile, wristwatch, and even your refrigerator speak to the cloud. It is the Internet of Things (IoT ) that refers to a network of physical objects that contain a sensor, software, and other technologies that connect and communicate data via the internet. Such things may include domestic devices and wearable, or even sophisticated industrial equipment, allowing them to communicate with one another and with their owners, which can, in many cases, be used to automate tasks and present new knowledge.

It’s convenient, until it isn’t. Crime scene investigators are now looking at the data of the IoT, such as the doorbell cameras, the smart thermostats, and the fitness trackers. During a murder, a heart rate spike may be registered by a smartwatch, and the GPS of a car may follow the track of a suspect.

Sounds futuristic, right? But there’s a catch: IoT forensics is a tangled mess.

The data in each device is stored differently; the evidence could be stored in servers in different countries and encrypted, and with data being erased that easily, each second counts. Researchers are creating new technologies to defend digital evidence, blockchain verifications, privacy-guaranteed infrastructure, and cloud-based solutions known as Forensics-as-a-Service (FaaS).

However, it is not only technical, it’s moral. Once your household appliances have been called to testify, where does privacy end and justice begin?

Inside the Real Crime Scene…

Turn off the TV, and enter into an actual investigation…. The floor is cold, and the lighting is faint; there is still the odor of chemicals. One detective in a brown suit takes pictures of a footprint before it gets washed away by the rain….

This is the actual crime scene work…. Quite on the contrary, it is motivated by patience and precision, and also burdened by budget reductions, staff shortages, and obsolete equipment. Recent studies reveal a widening gap that is increasingly growing between what is on the screen and what is on the tape. Crime scenes are chaotic, dynamic environments, and evidence that is living cannot manage without training, and not merely technology.

However, with the falling budgets, automation is coming to the forefront; Machines begin to take over what human beings are doing. That could be effective; however, it is dangerous. Forensic science is judgmental, and the human eye can see what the computers are blind to.

The actual question is: Is it possible to have justice when it is autopiloted?

When Media Becomes the Jury

The courtroom was formerly sacred; now it’s streamed. The Amber Heard and Johnny Depp case was the trial that was being watched by millions of people live, breaking down every glance, every tear, and every word. Memes became testimony under TikTok clips. The evidence frame by frame was dissected by YouTube experts.

It is the fresh appearance of the CSI Effect; social media does not simply report trials; it actually performs them. Viewers are jurors, liking, sharing, as well as judging in real time.

The danger? The boundary between the truth and entertainment is lost.

A viral video is more believable than a sworn statement. Facts are quick to be “liked and shared,” and propaganda is quicker than the facts, and justice in confusion becomes a popularity contest. It is not that people don’t care about the truth; they care too much. However, now caring with screens is different; it is not always the real story that prevails when the louder one is used.

Restoring Trust in Forensic Reality

It is not the solution to prohibit the real crime shows or shut down the internet. It is to educate individuals on how to narrate a story out of science. Media literacy is the key; people ought to be aware of what a real forensic work is like in the waiting, the uncertainty, the rules that make the evidence play straight. Lawyers and judges need to identify cases where jurors have very high expectations, and forensic scientists have to step out and talk directly to the general population.

There are already labs that are preparing for this future. They are experimenting with new systems to gather evidence, such as blockchain trails, which demonstrate the integrity of data. Scientists are developing frameworks of Forensics Readiness programs, which assist the investigators in gathering the digital evidence ethically and expeditiously.

Forensic readiness programs are pre-planned strategies that enable an organization to gather, conserve, and process digital evidence in legal, regulatory, or internal investigations. The purpose of these programs is to ensure that, in the event of an incident, the organization is equipped with quick and efficient response mechanisms to mitigate the effects of such occurrences, minimize business impacts, and reduce investigation costs. Additionally, the evidence collected is admissible and reliable. It is not about the ideal science. It’s trustworthy science.

Truth in the Age of Spectacle

Justice had been a matter of fact. Now it’s about visibility.

The reality is cut, edited, and sensationalized in the race for clicks on social media. But all true detective workers know, real facts do not shine. It conceals itself in the dull and stubborn details. The CSI Effect is, perhaps, not as massive as we believe it to be, but its shadow is long. It defines the kinds of justice in our eyes, our expectations of technology, and the way we determine guilt and innocence.

Perhaps, it is the true danger, not to believe a lie, but to hope for perfection. The fact that in real courtrooms, truth does not come in neon wrappings makes this possible. It arrives gradually and very quietly, one examination at a time.

“Sometimes the hardest evidence to find is not at the place of the crime, but what we want to believe.”

References:

- Schanz, K., & Salfati, C. G. (2020). The CSI effect and its controversial existence and impact: A mixed methods review. Reviewing Crime Psychology, 145-164.

- Rose, K., Eldridge, S., & Chapin, L. (2015). The internet of things: An overview. The Internet Society (ISOC), 80(15), 1-53.

- Stoyanova, M., Nikoloudakis, Y., Panagiotakis, S., Pallis, E., & Markakis, E. K. (2020). A survey on the internet of things (IoT) forensics: challenges, approaches, and open issues. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, 22(2), 1191-1221.

- Zahari, F., Harun, A., & Nasrijal, N. M. H. (2022). A systematic literature review on the usage of digital photography in the crime scene investigation process. Journal of Pharmaceutical Negative Results, 13(6), 2061-2069.

- https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2022-07-13/johnny-depp-amber-heard-defamation-trial-tiktok-documentary

More from the Author:

Blood Doesn’t Lie: How DNA and Serology Are Transforming the Legal Systems Worldwide

When Science Meets Silence: Decoding Post-Mortem Techniques in the Humaira Asghar Investigation