Culture, identity, and borders separate one country from another. They are all mere accidents of history and the products of specific circumstances- even the continents that seem so stable in their configuration and location are fickle in the eyes of the geologic time scale. Now separated across the Atlantic, there was a time when South America, India, and Australia were arm in arm, dancing around the South Pole. The evidence for this lies in the most unlikely of places.

I was at the entrance point of Zaluch Gorge, in the Western Salt Range, some 15 miles north of the city of Mianwali, on the 25th of August 2021. Due to the scorching heat, I had already finished half of my water bottle before starting the traverse. As I began, right in front of me, I saw little pebbles trapped inside the rocks rather peculiarly.

They seemed to be cut with a sharp knife by a master chef. These sharp cuts, in geological terms, are known as ‘faceting’ and are a work of no other than a glacier. When a pebble is trapped at the boundary of two glacial layers, the difference in the relative movement of the layers cuts the stone sharply. These pebbles were either deposited directly when the glacier melted or in the vicinity of a glacier by a stream originating from it.

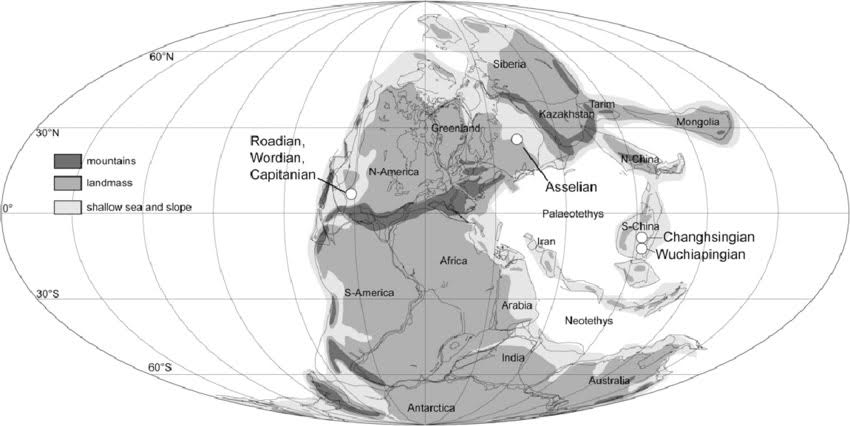

These rocks are reminiscent of times when the Indian Plate was covered with glaciers. At the same time, the streams flowed northwestwards towards the mighty Tethys Ocean, as indicated by the presence of the granite pebbles that originated from southern India and were brought to their present location by glaciers and streams.

Similar glacial sediments can be observed at many places in the Salt Range and along the Choa Saidan Shah road. Geoscientists correlate the glacial rocks of the Salt Range with Talchir Boulder Beds of India, and Al Khlata Formation of Oman and Saudi Arabia based on the presence of glacial signatures in all these rock units indicate their deposition in the proximity of the South Pole.

Such deposits during the Permian period (before dinosaurs appeared) have been reported from all the southern continents, which were part of the supercontinent Gondwana as it drifted slowly around the South Pole.

As one moves further into the gorge, it feels like traveling through time as every few meters of rock layers has condensed millions of years of Earth’s history. The world Is getting warmer, the signs of which are recorded as fluvial (river) deposits overlying the glacial ones in the form of sandstone beds of the Warcha Formation. It is a rock unit of considerable thickness and spatial extent, indicating a meandering river that emptied into the Tethys Ocean.

Soon (geologically speaking), the sea level started to rise. The earlier Warcha Formation river deposits began to be buried by the ocean sediments full of fossils, including brachiopods, bivalves, ammonites, and gastropods. This composite rock unit is called the Zaluch group, named after this very gorge, where it has the best-exposed outcrops.

For me to be holding these fantastic fossils, many factors needed to come together, e.g., an organism dying in a manner that allowed it to be fossilized, if the fossils right in front of me would have been eaten by a predator or destroyed by the wave activity. I wouldn’t be observing them here today. Most importantly, the collision of the Indian tectonic Plate with the Eurasian tectonic Plate resulted in the formation of this crack (Salt Range Thrust), along which millions of years old rocks came up and were exposed to the surface.

I collected a few fossils and went on to look for shade. At some distance, under a bit of bush, I found a shepherd resting while his sheep were jumping across the bare slopes in search of grass. I went towards him; he offered me a cup of tea, and we started chatting. During our conversation, I realized that he did not know his area’s geology and fossils.

He was somewhat concerned about his livelihood and his children’s education – questions much more essential than thinking of some long-gone organisms. I told him about the remarkable history of the rocks in his area. However, he seemed disinterested in my stories, and the discussion circled back to politics, scarcity of jobs, and the deteriorating financial situation of the region.

As a final attempt to fire his curiosity, I told him that this piece of land we are sitting on right now has traveled more around the globe than both of us and probably more than most of its inhabitants. However, this attempt was also in vain; he looked at me as if I had gone completely crazy. I thanked him for the tea and stood up to continue my journey.

With the parting greeting, however, he suggested looking at a rock at the top of the mountain. ‘There are sparrow’s beaks in the rock,’ he exclaimed. I got curious and hurried to see it for myself. At the top, many brachiopod fossils protruded from the rock, and as had accurately described, they seemed like beaks stuck in the rocks – a life frozen in time.

Earlier this year, I was reading our former prime minister Imran Khan’s book ‘Pakistan: A Personal History’ where he briefly mentioned the Salt Range and how much he enjoyed hunting there. Still, I didn’t come across his vision for promoting and preserving the area’s geological heritage.

Just at the back of Salt Range sits Namal University, one of the best institutes in Pakistan, but after discussion with some students there, I realized that they were as oblivious of the geological heritage of the area and as caught up in their problems as the shepherd I had met in the Zaluch gorge. However, two months before the Zaluch Gorge trip, I had quite the contrary experience.

I went to Villuercas Ibores Jara, UNESCO Global Geopark in Extramadura, Spain, as part of my Erasmus Mundus program. It was a hot summer day when we reached a local primary school within the geopark. To my surprise, the children there were well aware and quite excited about the local geology, ecosystems, and biodiversity. On school walls, with the help of local artists, they had painted different ancient ecosystems as preserved in the rocks around the school. They were grounded, took pride in their heritage, and were aware of the changing local ecosystems.

Later on in the trip, we visited the local olive farms, wineries, livestock farms, and some small local businesses. The vineyard owner explained to us the formation of soil that resulted in land perfect for grapes. His 8-year-old daughter, who grew up at the local livestock farm, explained the groundwater flow; every single person there was so connected to their land and took ownership to protect and preserve it for future generations.

On one particular occasion, we met some school children aged 6 to 14 making little road signs indicating sites of detailed geological or biodiversity interest and how to take care of natural heritage. In a tiny town, the buildings’ walls were covered in tiles, mined from a local quarry, full of ichnofossils of trilobites (imprints of their movement).

The thing I found most astonishing was the awareness of natives about their surroundings – their history, culture, and how they incorporated all of it into tourism and their economy. Schoolchildren explained to us the local biodiversity, indigenous plants, and how the birds prefer to make their nests in local plants.

Understanding how the world has changed and will continue to change geologically, climatologically, and culturally is crucial to put ourselves in comparison to the immense expanse of time. Geoparks are vital in getting these concepts across. Talking about Pakistan’s geo-heritage, it would not be an overstatement that we have one of the best and most well-preserved geological records in the world. Still, despite the present tourism-friendly atmosphere, we haven’t developed a single UNESCO Global Geopark in Pakistan.

Salt Range, Pakistan, has recorded the history of the Indian Plate as it traveled from the South Pole, covered with glaciers, to its current location in the present day, and all the stories it saw during this time are hidden in its rocks. Not only rocks, but the temple of Katas Raj, Nanda fort near which Al-Beruni measured the circumference of the Earth, Takht-e-Babri, and even the Khewra Salt Mine shows the progress of human civilization. The changing cultural landscape for thousands of years nested in changing geological landscape for millions of years, and layers upon layers of stories hidden to be told.

Along with the Salt Range with its sedimentary rock record of pre-Cambrian to Recent, Pakistan is gifted with myriad other geological wonders, including mantle rocks exposed along Karakoram highway at various places, the Kohistan Island Arc, Cambrian Nowshehra Reef Complex just next to Nowshehra city, some of the largest glaciers, and mud volcanoes to name a few.

The geologic heritage is suffering, and we are facing the worst natural disasters, including landslides, the outburst of glacial lakes, earthquakes, floods, and seawater intrusion. Understanding their causes is essential for the public to reduce the deaths and damage caused by our ignorance.

a) Glacial rocks of the Salt Range containing pink faceted pebbles of Nagarparker Granite (clean cut shows glacial action) (courtesy: Muhammad Faheem)

b) The alternating pebbly and sandy beds show changing water energy that deposited these rocks (these beds were deposited horizontally, but the tectonic activity moved them to their present vertical position)

c) Ammonite (courtesy: Muhammad Faheem)

d) Belminites (there is a myth about these fossils that they are bullets used against the British army)

e) Trace fossils (show the movement of ancient organisms)

On the biodiversity front, we are facing challenges, too, e.g., half of Islamabad suffers from pollen allergy during spring because of Broussonetia papyrifera (Paper Mulberry), an invasive species planted to make the city green. Today, the city is green, but many birds have left, and the residents suffer every spring. It is the need of the hour for the government to divert its focus from cashing in on the scenic mountain peaks of the North and instead prioritize the geological heritage for tourism, education, and economic development.

The information on the geology of Pakistan is not scarce, but it is somewhat trapped in scholarly journals and the geology departments of academic institutions. If given the opportunity, academia can play a massive role in bringing geological awareness to the forefront. Strong coordination among PTDC, Geological Survey of Pakistan, universities, local schools, and media can help locate, preserve, and promote our heritage.

Thinking about all the possibilities to preserve and promote the geological heritage of Pakistan, I did not realize that the sun had started to hide behind the hills. I sat on the cliff’s edge and played the ghazal ‘Waqt ki qaid mai zindi hai Magar, chand gharian Yahi Hain jo azaad hain.’ I could not stop thinking about the fantastic creatures whose fossils were peaking out of rocks in front of me and about the paleo-landscapes. It was a feeling of time and space transcending.

Nature, love, and creativity know no boundaries: I was enjoying a song written by a Pakistani poet, and sung by an Indian singer, and while listening to it, I was wondering about ancient times when this piece of land was traveling across the ocean to its

present destination. The rock strata beneath me contain the stories of so many different worlds, worlds where our species was not even in the picture, let alone the star or villain of the picture. Yet, somehow, all the stories of earlier worlds intertwined to give rise to our story. A humbling and profound realization of connectivity and belonging.

We are the first species with not just the ability to alter the planet on a geologic scale but also the mental ability to foresee the consequences. We are aware of the link between our actions and each of the Earth’s possible futures. I wish all my country fellows could feel the same and celebrate their mountains, rivers, and rocks.

After finishing the field trip, as I was coming out of the gorge, I happened to see a graveyard nearby, and, partially out of habit and curiosity, I decided to visit it. Inside, I noticed something unique about the graves there. Unlike most tombs in Pakistan were built with concrete and finished with a nice tombstone with the name and date of death of its inhabitant marked. Several graves were decorated with Permian limestone, which is full of fossils. At the same time, the monument on top was a reddish rock full of trace fossils, a reminder of the inevitability of death and the preservation of life in nature – one by us, the other by nature itself.

Also Read: IN TODAY’S WORLD, ANTHROPOLOGY IS MORE IMPORTANT THAN EVER

Sikandar is a final-semester student of Erasmus Mundus Joint Master Degree PANGEA (Palaeobiology, Applied paleontology, Geoconservation) (University de Lille, France; University of Athens, Greece) and is currently working on coccolithophores of Eastern Mediterranean. Prior to that, he received Stipendium Hungaricum scholarship to attend MSc. Hydrogeology program at Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary. He writes on various topics in earth sciences on his Instagram @geotalkies.