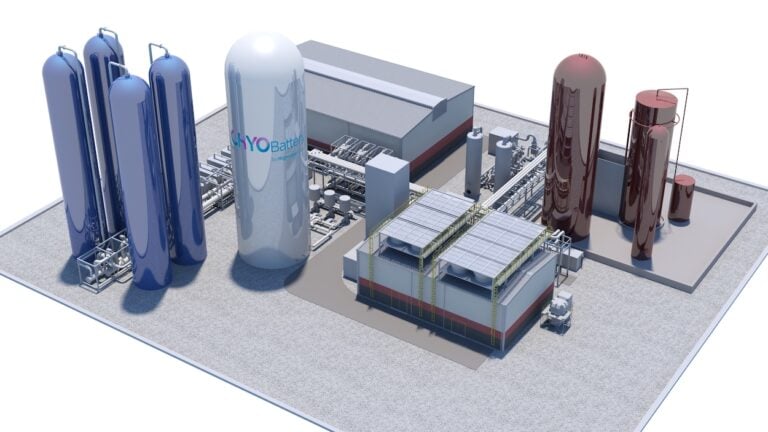

Long-Duration Energy Storage or LDES is rapidly moving out of the labs and into real-world deployments, capturing the attention of governments, tech giants, utilities, and energy markets worldwide. Once a niche concept, LDES is now being touted as the missing link in the transition to 100% clean energy.

What is LDES, and why does it matter now?

Long Duration Energy Storage (LDES) encompasses the technologies designed to store vast amounts of energy and release it over extended periods, often 8, 12, or even several days, rather than the few hours typical of conventional batteries. LDES takes various forms of energy, including thermal, electrochemical, chemical, and mechanical. 1 These systems tackle one of the greatest challenges of renewable energy and intermittency, the reality that solar panels don’t generate power at night and wind turbines don’t always spin.

Unlike short-duration battery systems, LDES can bridge energy gaps overnight, during cloudy weather, and even during seasonal lows in renewable generation, making it indispensable for highly renewable grids.

Cutting-Edge Innovations Hit the Spotlight

China’s clean-tech leader HiTHIUM recently unveiled three major LDES breakthroughs at its annual Eco-Day event, including the world’s first 8-hour-native storage solution and a high-capacity 8-hour LDES cell designed for grid and AI data center integration. These innovations aim not just to store energy for long but to deliver it reliably in real-time, even to power-hungry digital infrastructure, not just in China, but around the globe.2

Policy and Market Momentum

Governments and regulators are accelerating policy actions to support long-duration energy storage (LDES) as part of efforts to bolster grid reliability and integrate higher shares of renewable power. In Southern Australia, officials have opened the first competitive tender under the Firm Energy Reliability Mechanism (FERM), 3 which targets 700 MW of long-duration storage capacity across staggered operational dates between 2028 and 2031.

The technology-neutral tender, which can include batteries and other dispatchable capacity able to deliver sustained output. Forms a cornerstone of the state’s strategy to secure more reliable, affordable electricity and manage the variability of wind and solar generation. The selected projects will be offered 15-year contracts to help underwrite revenues and support project finance, with bid submissions closing in late 2025 and outcomes expected in early 2026.

Meanwhile, in the United Kingdom, energy regulators are developing incentives to attract private investment into LDES at large scale. Ofgem, 4 in coordination with the UK Government’s Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, has introduced a cap-and-floor revenue support regime for qualifying LDES projects, a model that sets minimum guaranteed revenues while capping excessive returns to protect consumers.

The first application window opened in April 2025, and a multi-criteria assessment framework for selecting projects is being finalized, with formal cap-and-floor awards expected by mid-2026. Early eligibility assessments have already been shortlisted for several large-scale schemes, some totalling gigawatts of potential storage capacity, for further evaluation ahead of final selection.

These moves suggest that broader global recognition of LDES is a crucial infrastructure for energy systems transitioning away from fossil fuels. By underwriting long assets and offering revenue certainty, South Australia’s FERM and the UK’s cap-and-floor mechanism aim to reduce investment risk and catalyse the deployment of storage capable of delivering power for eight hours or more, helping to smooth peak demand and balance intermittent wind and solar output. Such regulatory innovation is seen as essential to unlocking the next wave of clean energy projects and ensuring grid stability as renewable capacity rapidly expands.

Tech Giants Join the Race!

Technology giants like Google have announced a landmark collaboration with Arizona’s Salt River Project (SRP) to advance non-lithium long-duration energy storage (LDES) technologies, 5 a step forward that could help accelerate the deployment of next-generation grid storage solutions. Under the first-of-its-kind research partnership, Google has committed to funding a portion of the costs for LDES pilot projects deployed on SRP’s electric grid. While also analyzing operational performance data and helping shape research and testing plans for these emerging systems.

The initiative focuses on storage technologies that can deliver power for extended periods far beyond conventional lithium-ion battery durations, which might help utilities better integrate renewable generation and improve grid reliability.

The collaboration builds on SRP’s broader strategy to explore a range of energy storage options that support its sustainability and reliability goals, including its commitment to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. While Google pursues its ambition of operating its global data centers and offices on 24/7 carbon-free energy and reaching net-zero emissions across its operations and value chain.

Both partners have highlighted the importance of LDES in stabilizing stressed grids and enabling deeper renewable energy penetration, particularly as utilities seek solutions. It can deliver energy for 10 hours or more. SRP has previously issued requests for proposals for non-lithium LDES demonstration projects, and this collaboration with Google could help bring multiple such projects closer to commercial reality.

Global Projects Demonstrate Real-World Impact

From a global perspective, across the continents, long-duration energy storage is beginning to translate from concept to concrete investment. Hydrostor, a Canada-based energy storage developer, recently secured US$55 million in fresh funding to advance its 200-megawatt compressed-air LDES project in Australia, marking a significant step in scaling storage technologies that run beyond traditional batteries.

The funding also follows other developments in long-duration storage solutions, like Form Energy, which began construction of its first iron-air battery facility in West Virginia in 2024, while Energy Vault commissioned several gravity storage systems globally through 2023. 6

At the same time, momentum is building in Africa too, where LDES is emerging as a practical solution to chronic power shortages. In Nigeria, an initial 8 MWh long-duration storage project is being deployed to strengthen the grid reliability and cut reliance on costly, polluting diesel generators. Together, these developments highlight how LDES is no longer confined to pilot labs in advanced economies but is increasingly being tailored to meet diverse energy challenges, from stabilizing renewable-heavy grids in Australia to delivering dependable power in emerging markets.

LDES, Growing Climate and Economic Imperative

Industry experts argue that LDES is far more than a technical solution for balancing power grids. Conversely, it is emerging as a strategic, economic, and climate instrument with a wide-ranging impact. By storing clean electricity for hours or even days. LDES enables deeper penetration of renewables, reduces dependency on fossil-fuel peaker plants, and shields energy systems from price volatility and supply shocks.

At the same time, it opens new investment pathways, supports industrial growth, and helps countries meet climate targets while keeping power reliable and affordable for every sector, positioning LDES as a cornerstone of the global energy transition rather than just another piece of infrastructure.

What’s next?

With investment momentum building, new storage technologies nearing commercial maturity, and governments crafting clearer, long-term revenue frameworks, industry observers increasingly see 2026 as a pivotal moment for long-duration energy storage. If these trends converge as expected, LDES could finally bridge the gap between intermittent renewable generation and round-the-clock increasing energy demand, turning wind and solar into dependable, always-available power.

More than a technical milestone, this shift would redefine how electricity systems are planned and operated, whilst providing the backbone for resilient, affordable, and decarbonized grids and signaling a decisive step away from fossil-fuel dependence toward a more secure energy future.

References:

- Long Duration Energy Storage Council (LDES Council)

- HiTHIUM Introduces Innovative Long-Duration Energy Storage Solutions at 2025 Eco-Day – Third News

- AER Submission – Firm Energy Reliability Mechanism, 20 December 2024.pdf

- Long-duration electricity storage | Ofgem

- We are shaping the future of long-duration energy storage technologies through a new partnership in Arizona.

- Hydrostor nets $200M for its long-duration energy storage ambitions – Energy Storage

More from the author: Marine Animals Die From Much Smaller Plastic Doses Than Previously Believed

Also, read: The Role of Finance in the Clean Energy Shift: An Interview with Muhammad Ali Qamar